Introduction of the postage due stamp

Ensuring the proper collection of taxes on local mail was a major concern for the Administration. Since it was not feasible to assign an inspector to every post office—only the larger ones had such oversight—errors and malpractices often went unnoticed for an extended period.

To address this issue, the Minister of Finance issued a decision on 14 October 1858, followed by a decree on 15 November 1858, significantly reducing these errors, if not eliminating them entirely. As a result, the Chiffre-Taxe (postage due stamp) was introduced on 1 January 1859 to facilitate the taxation of unpaid or insufficiently paid letters.

These stamps were systematically registered, and the Administration maintained a detailed inventory, tracking both the stamps themselves and the post offices to which they were assigned.

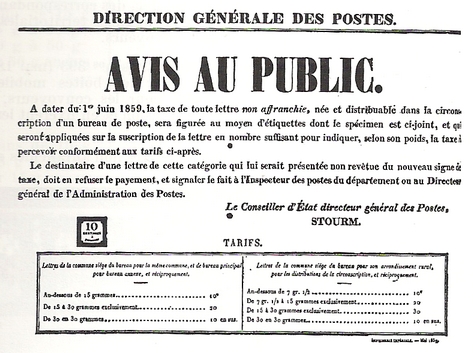

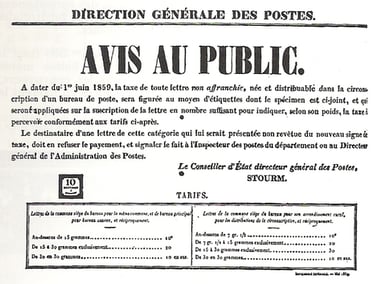

Initially, from 1 January 1859, Chiffre-Taxe stamps could only be used within the rural district of a given post office. For correspondence exchanged between two rural districts within the same Postal District, taxation still had to be carried out manually. However, due to the success of this measure, the Administration decided to extend the use of the Chiffre-Taxe to the entire Postal District by decree on 25 April 1859, effective from 1 June.

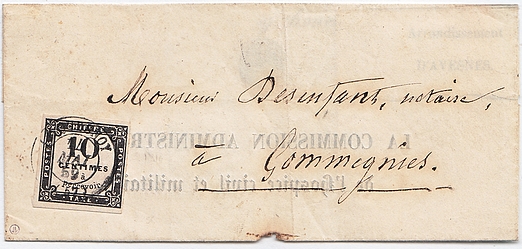

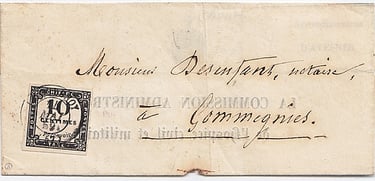

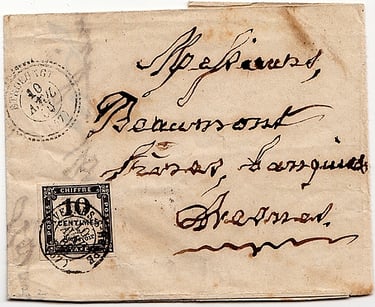

1859: Letter from LE QUESNOY for GOMMEGNIES rural commune dependent on LE QUESNOY. Here, the Chiffre-Taxe is of the lithographed type.

Circular No. 106 of December 1858 (BM No. 40) specifies that the official cancellation method for the Chiffres-Taxes is either the date stamp or the OR stamp of the rural postman. It further states that a single strike of the date stamp is sufficient and that applying a second strike on the letter is unnecessary.

However, Circular No. 124 of April 1859 introduces a change: from 1 June 1859 onwards, Chiffres-Taxes should not only be canceled with the date stamp but must also receive a second strike for validation.

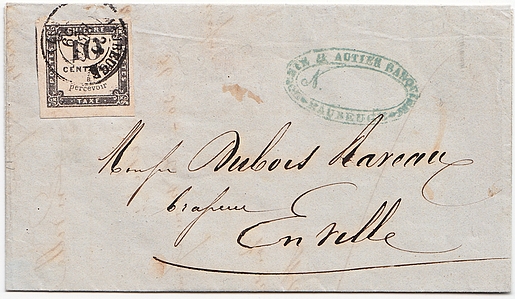

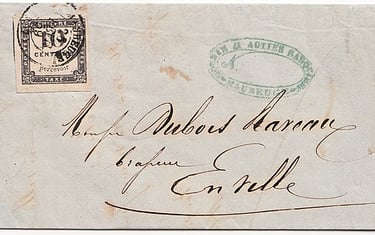

1859: Letter from and to MAUBEUGE dated February 1859. At this date the Chiffres-Taxes can be used only within the rural district of a post office.

This Chiffre-Taxe was printed in lithography. The short time between the decree and the planned introduction of these stamps meant that the authorities had to use a quick printing method. The lithographed type can be recognised by the very thin wording "à percevoir" ("to be collected"). On the typographed type, which appeared in February 1859, the printing is thicker. Before 1 June 1859, letters circulating within the town of the post office did not have to bear a Chiffre-Taxe.

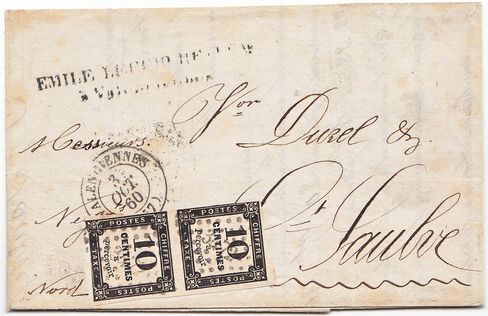

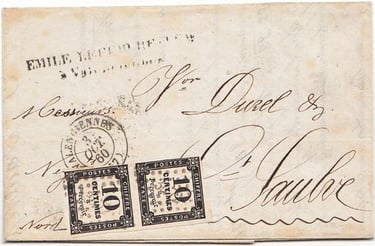

1860: Letter from VALENCIENNES to ST SAULVE weighing 15 g. Here, the VALENCIENNES post office is in complete irregularity, since it cancels the Chiffres-Taxes with its small numerals whereas since 1st June 1859, it is supposed to cancel them with its date stamp.

If the Chiffres-Taxes appeared on letters exchanged between a post office station and the head post office within the same Postal District, they were always applied and canceled by the head post office, regardless of whether the letter originated from the post office station (§ 2 of Circular No. 124).

1860: Letter mailed at the ETROEUNGT post office station for AVESNES (head post office). From 1st June 1859, Chiffres-Taxes could be used on local mail circulating between 2 rural districts.

When the rural postal service was introduced in 1830, rural postmen were not permitted to deliver letters in the suburbs of towns, even if their route took them through these areas.

The General Instruction of 1832, specifically Article 546, sought to establish a clear distinction between the local and rural postal services. Rural postmen were responsible for delivering letters, most of which were subject to the additional rural decime, while town or local postmen handled correspondence subject to local postage rates.

By January 1847, with the abolition of the additional rural decime, maintaining two separate postmen—one for local deliveries and another merely passing through—became increasingly difficult to justify, particularly in towns and their suburbs.

Over time, practical service demands led to adaptations, allowing rural postmen to operate in localities with a post office or on the outskirts of larger towns.

Today, we associate the outskirts of a town with dense, urbanized areas. However, in the 19th century, town suburbs often featured a mix of populated zones and largely rural landscapes.

Circular No. 324 of April 1847, while reaffirming Article 546 of the General Instruction of 1832, ultimately authorized rural postmen to serve town outskirts, provided these areas were located outside the city walls.

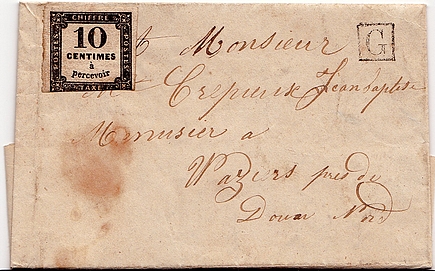

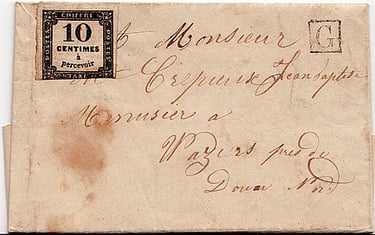

1862: Letter written in the hamlet of Frais-Marais and addressed to the rural commune of WAZIERS. The hamlet of Frais-Marais was a part of the town of DOUAI, whereas WAZIERS was an independent rural commune. One of the rural postmen from DOUAI therefore served Frais-Marais as well as WAZIERS on the same round. Moreover, Frais-Marais and WAZIERS border each other. Frais-Marais had an urban letterbox (known as an additional letterbox) with the G code.

The Chiffre-Taxe should have been cancelled with the postman's OR stamp.

Finally, the Administration had foreseen the case where the Chiffres-Taxes applied to the letters could not be recovered. Circular no. 106 of December 1858, and in particular paragraph 44, states:

"It will often happen that the value of the Chiffres-Taxes affixed to the letters cannot be recovered, and that these letters will have to be returned, either as rejected or to a new destination.

As a general rule, any Chriffre-Taxe applied to a letter which, for whatever reason, could not be delivered, will be cancelled a second time by two strong pen strokes drawn in a cross +, and the tax that this Chiffre-Taxe represented will be reinstated on the letter by hand."

The operating procedure imposed by circular no. 106 was complicated, and many offices did not apply it fully, in particular by not re-establishing by hand the tax expressed in the Chiffre-Taxe.

1860: Postage due letter posted at ROUBAIX for ROUBAIX. As the addressee was in SASSEGNIES near BERLAIMONT, the letter was sent back with territorial postage, therefore taxed at 30 c.

This is the perfect application of what was required by circular no. 106.