The rural decime

Specific case of the rural decime

When the rural postal service was introduced, and until 1 January 1847, a letter traveling between two rural districts—provided it was sent to or from a commune without a post office—was subject to an additional tax of 1 decime (10 centimes).

This surcharge, known as the additional rural decime, was a fixed amount added to the standard postage and was intended to help finance the rural postal service.

The imprint indicating the tax could appear in two colors: black if the letter was addressed to a rural commune and red if it originated from one (circular no. 36, 18 October 1834).

While the additional rural decime was justified when rural districts were widely separated and belonged to different postal districts, it became problematic when applied to letters sent between communes within the same district. In such cases, the combined cost of postage and the additional tax could become excessive.

A rural district typically spanned around ten kilometers: “A commune could not be directly served by the post office it depended on if it was more than 10 to 12 km away…,” according to postal regulations.

This distance was both short and long—especially given that most people traveled on foot—and many individuals felt that the tax was unwarranted in such cases.

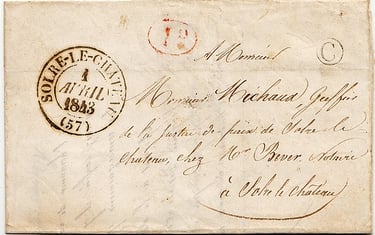

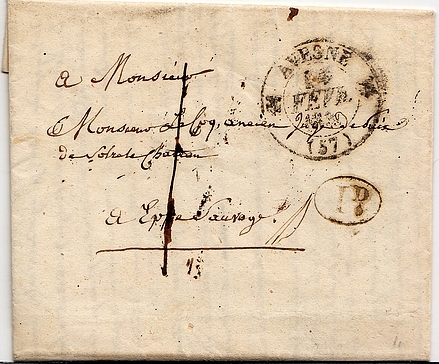

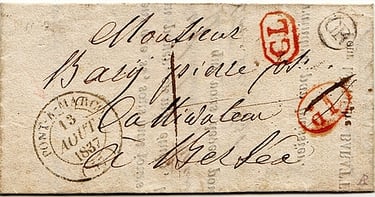

The additional rural decime used correctly

1836: Letter posted at AVESNES for EPPE-SAUVAGE. The commune of EPPE-SAUVAGE depended on the post office station of TRELON which itself depended on the head post office of AVESNES. The additional rural decime is justified here because the letter circulated from one rural district to another and was bound for a commune with no post office.

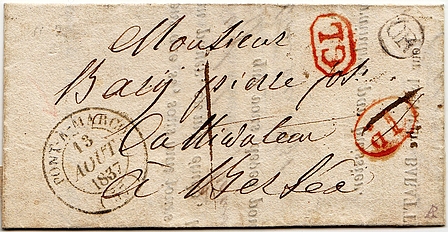

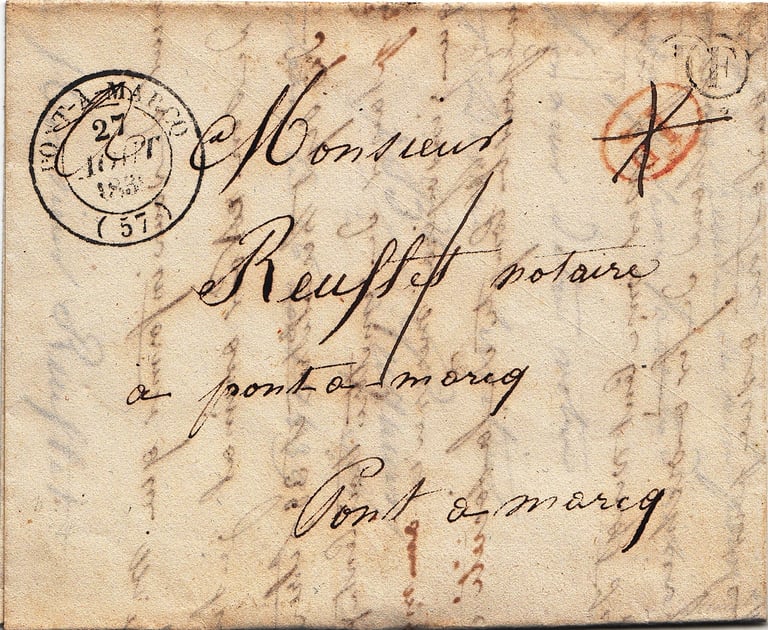

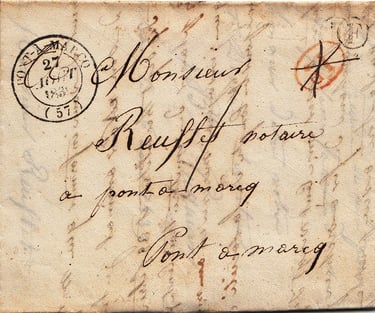

1836: Letter from LILLE to PONT A MARCQ. This rural commune depends on the SECLIN post office station (opened in February 1830), which depended on the LILLE head post office. This letter therefore circulates between 2 rural districts and is addressed to a rural commune with no post office. The additional rural decime is therefore justified. The rural decime imprint is in black ink, which means that the letter is addressed to a rural commune.

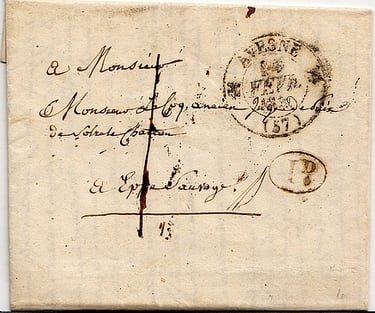

Back of the letter

Without revisiting the mechanics of the rural decime, it is evident that applying this tax posed challenges for postal clerks responsible for letter taxation. Users frequently lodged complaints about excessive charges, prompting the Administration to intervene multiple times. Despite repeated warnings to post offices, issues with the tax's application persisted for an extended period.

The additional rural decime was finally abolished on 1 January 1847.

Corrected errors

1837: The rural decime had to be applied to letters circulating between two rural districts and coming from or going to a commune without an office.

In this case, the letter was given to the rural postman during his round to TEMPLEUVE (OR stamp) and was to be sent to BERSEE. These two towns were part of the rural district of the PONT A MARCQ post office. The rural decime therefore did not apply, and the error was corrected by a stroke of a pen.

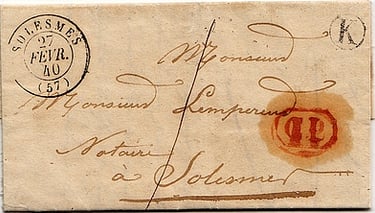

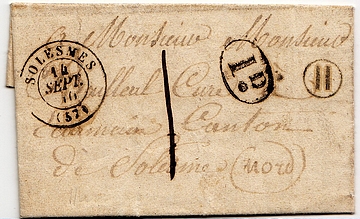

1840: Letter mailed in the village of BERMERAIN (letter-stamp K) for SOLESMES. The postman first applied the stamp of the rural decime and then, realising his mistake, masked it with the imprint of the CL stamp. BERMERAIN is part of the rural district of SOLESMES, so the rural decime does not apply.

1839: Letter from the village of HAUSSY to SOLESMES. Here also the rural decime had been applied by mistake and then masked. It seems that the SOLESMES office had some problems understanding whether or not the rural decime should be applied.

Most of the time, errors in applying the rural decime were corrected, as they were often due to simple carelessness. The rural decime stamp closely resembled the CL stamp, and clerks responsible for taxing letters had to handle multiple stamps, some of which were applied to outgoing mail while others were not. Given the high volume of mail processed, mistakes were inevitable.

However, some errors went unnoticed or uncorrected, leading to accounting discrepancies for post offices.

It is important to remember that letters were sent postage due, meaning the recipient's local post office collected the tax upon delivery and applied the additional rural decime when necessary. Many local letters were addressed to businesses, civil servants, or lawyers—people familiar with postal rates—who refused to pay more than what was required.

Taxes, including the rural decime, were recorded in advance in accounting registers. When a recipient rightly refused to pay an incorrectly applied rural decime, two possible scenarios unfolded:

The addressee refused the letter entirely, resulting in its return to the sender at the post office's expense, as no postage had been collected.

The addressee refused to pay only the additional rural decime, prompting the postman to return the letter to the office. Once there, clerks had to correct both the tax and the account books before resubmitting the letter.

If such errors occurred repeatedly, the addressee could file a complaint with the Administration, which would then issue a formal warning to the post office manager.

These mistakes were also reflected in account books, which were regularly audited by Post Office inspectors. In such cases, the manager—who was personally responsible for accounting accuracy—had to justify any discrepancies.

However, it should be noted that local letters often escaped scrutiny from the authorities, even when recorded in accounts, because they circulated within the rural district of the same post office. In these cases, the post office itself acted as both the creator and collector of the tax.

1839: Letter mailed in the village of MONS EN PEVELE to PONT A MARCQ. The rural decime was applied by mistake instead of the CL stamp. The correction was made by crossing out the rural decime stamp.

Uncorrected errors

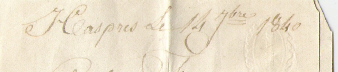

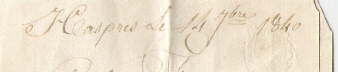

1840: Letter written in HASPRES for the priest of the village of ESCARMAIN.

The stamp letter H does not correspond to the village of HASPRES which, moreover, depends on the post office of BOUCHAIN and not SOLESMES. It therefore seems that the sender of the letter, who lived in HASPRES, wanted to save the addressee 10 c (the rural decime). He therefore mailed his letter in SAULZOIR (letter with H stamp) 3 km from HASPRES.

However, this was without taking into account the difficulties encountered by the clerk in charge of taxing at the SOLESMES post office. The latter nevertheless applied the additional rural decime in an unjustified manner.

Misuse of the rural decime

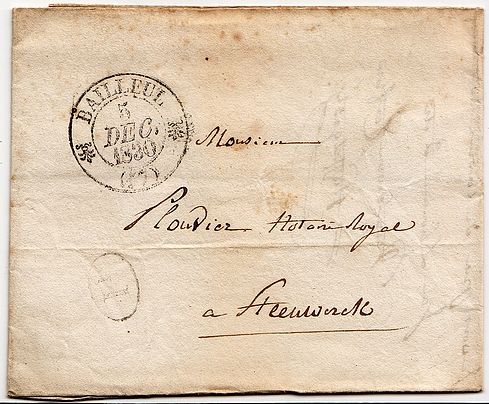

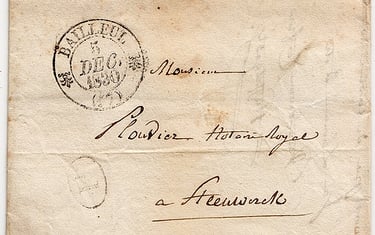

1830: Postage due letter from BAILLEUL to STEENWERCK. Only the rural decime imprint is present on the letter. The colour code is correct, as the black ink means that the letter is addressed to a rural commune. It is the use of the rural decime that is incorrect, as it simply represents the postage and not an additional tax.

The rural decime stamp was occasionally used for an unintended purpose—as a local 1-decime tax stamp. This practice was observed in several post offices across different departments. Rather than an official policy, it was a matter of convenience, as the Administration had explicitly forbidden its use in this way. The rural decime stamp was designed solely to indicate an additional tax, not to represent the standard postage of a letter.

Some post offices had commissioned their own "1" stamp at their own expense to streamline the taxation of local letters. However, for this investment to be justified, the volume of taxable letters had to be sufficiently high.

Some postal directors may have considered it unnecessary to create a separate "1" stamp locally, believing that the rural decime stamp could serve the same function just as effectively.