Local rates and rural postal service

Before 1830

Before 1830, rural mail service was virtually nonexistent. While it was possible to receive mail at home in a rural commune—outside the locality where the post office was located—delivery was typically handled by messengers paid by communes or prefectures. When these messengers delivered mail to private individuals outside official arrangements, they charged fees based on mutual agreement.

For private recipients, delivery costs were high, as postage fees had to be paid in addition to home delivery charges. To avoid these expenses, individuals could choose to collect their mail from the nearest post office. However, many letters went unclaimed, leading to an estimated 300,000 discarded letters annually.[1]

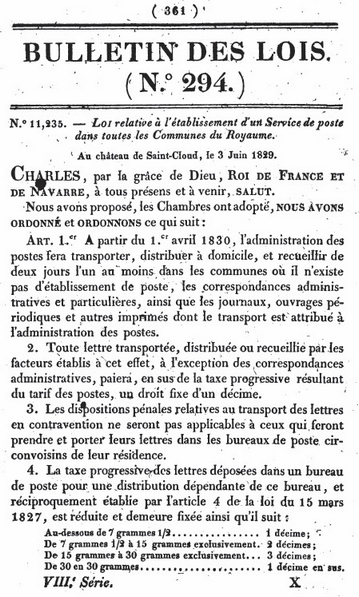

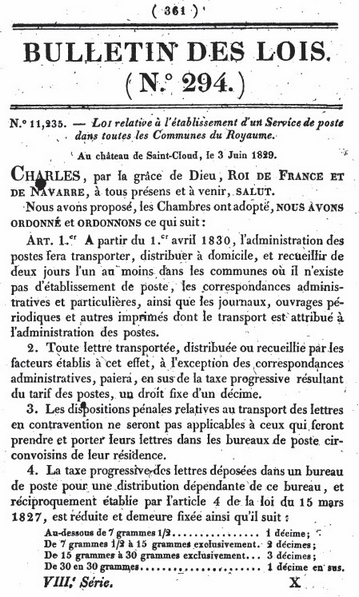

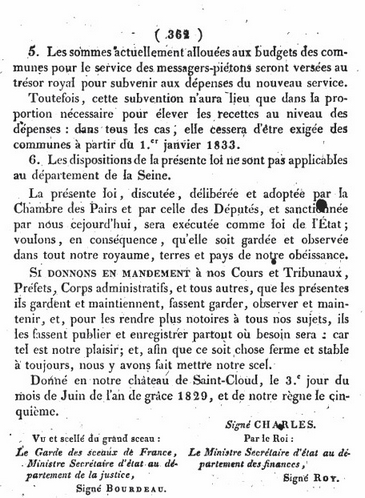

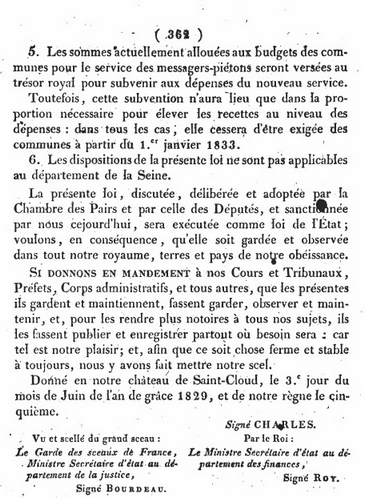

On 1 August 1828, Charles Sapey, MP for the Department Isère, published his "Opinion on the Project to Complete the Postal Service in France" , proposing home delivery every two days in towns without a post office. His proposal inspired the rural postal service law, which was passed on 3 June 1829 and came into effect on 1 April 1830.

1830 and after

Starting on 1 April 1830, the government installed letterboxes in over 35,000 communes that lacked a post office. To facilitate mail delivery and collection, 5,000 postmen were recruited, some of whom had previously worked as messengers. These postmen were tasked with delivering and collecting mail every two days in these rural areas. Additionally, in March 1830, the Post Office issued an Instruction on Rural Service to guide postal employees in implementing the new system.

This bi-daily mail service continued until 1832. However, the law of 3 April 1832 (§47) mandated that, starting on 1 July 1832, rural postmen's rounds should become a daily service. In practice, this transition was gradual. For instance, in the Nord department, it took until 1850—18 years after the law’s passage—for every rural commune to receive daily mail delivery.

Application of the local rate

The local postage rate was lower than the territorial postage rate in four specific cases:

Within the same town: When a letter was sent within the limits of a town that had a post office, regardless of its classification.

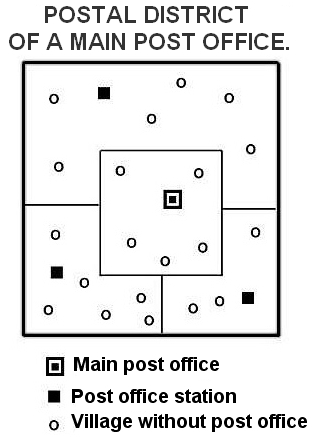

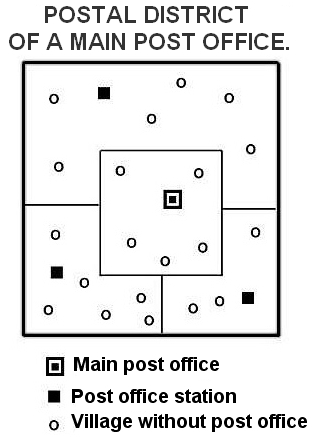

From a post office to its dependent communes: When a letter was sent from a town with a post office to communes without a post office that were dependent on that office. The town and its attached communes together formed the rural district of that post office.

Between rural districts within a postal network: When a letter circulated between the rural district of a head post office and the rural districts of one or more post office stations under its authority. At the time, a head post office could oversee several post office stations. The combined rural districts of these stations and the head post office formed a Postal District.

These first three cases accounted for 18 possible routes where the local postage rate applied.

Between two head post offices and their rural districts: This situation was less common, with only 19 instances where two provincial head post offices fell under the local rate system for letters exchanged between their rural districts. This special rate was known as the Joined Head Post Offices (Recettes Réunies) rate.

In the Nord department, two such cases existed:

Lille / Moulin-Lille / Fives

Valenciennes / Anzin

These post offices were so close to each other that the public questioned why the territorial rate should apply instead of the local rate.

The introduction of the rural postal service required significant expenditure, which was offset by additional revenue and a fixed tax.

This tax, known as the Additional Rural Decime, was applied only once per letter, even if the letter was both collected and delivered in rural localities (as stipulated in Article 10 of the Instruction of 1830). The tax remained in place until 1 January 1847, when it was abolished following the law of 3 July 1846.

From the beginning, most local correspondence was sent postage due, as there was no financial advantage to prepaying postage—postage due and postage paid were identical in cost. The same principle applied to territorial postage. At the time, it was assumed that the Post Office had an incentive to deliver postage-due letters, as it would only collect payment upon delivery. In contrast, if postage was prepaid, the Post Office had already secured the payment, potentially reducing its motivation to ensure delivery. Additionally, prepaying postage required a visit to the post office, which could be inconvenient due to distance.

The introduction of the postage stamp did not initially change this practice. However, on 1 July 1854, the postal administration introduced a franking incentive for the territorial rate, offering a discount for prepaying postage. This initiative encouraged more people to send franked letters, increasing revenue for the Post Office.

Despite this, most local letters continued to be sent postage due. It was not until 1 January 1863 that a similar franking incentive was introduced for the local rate. This, too, proved successful, significantly increasing the number of franked letters.

After this reform, no major changes were made to the local rate until 1 May 1878, when it was officially abolished.

The rural postal service in the Nord

The Nord department, though densely populated, remained largely rural throughout the 19th century. Rural inhabitants were relatively isolated from the State, with little awareness of events beyond their immediate surroundings—even within their own department. The rural postman served as a vital link between the Administration and the countryside. Dressed in his official uniform, he not only delivered mail but also brought news and embodied the presence of the State, helping to reduce the isolation of rural communes.

If this was true for the Nord, it was even more so for predominantly rural departments. The local postal rate was closely tied to the development of the rural postal service. However, the implementation of rural mail delivery in the Nord was not without challenges. When the authorities mandated daily postal rounds in 1832, the reality was far different for many communes. It took until around 1850—18 years after the decision—for all communes in the Nord to receive daily deliveries. In 1832, the lack of post offices and the remoteness of many towns made daily rounds impractical. Some post offices oversaw rural districts with more than 30 municipalities, and delivery routes were often inefficient. With too few rural postmen, mail frequently arrived late in the afternoon.

Despite being a significant improvement for rural residents, the rural postal service remained a logistical challenge for the authorities.

Interestingly, while rural inhabitants valued the postal service, the number of local letters (those sent within the same Postal District) in the Nord remained relatively low. According to a statistical survey conducted in 1847, fewer than one local letter (0.3) was sent per inhabitant per year. This figure was extrapolated from a two-week survey conducted from 15 to 28 November 1847. During that period, of the 42,147 letters sent to communes in the Nord:

33,686 were territorial letters,

8,461 were local letters.

The 1847 postal survey also provided valuable insights into rural mail distribution. It detailed the volume of mail sent and received by each commune and revealed that letterboxes were not always located at town halls, as might have been expected.

Need to learn more?

The books are few in number, but very comprehensive. They will enable you to make rapid progress on the subject:

- Histoire de la Poste en milieu rural: Marino CARNAVALE-MAUZAN. GENOBLE 1994

- Le port local de la lettre ordinaire en Province. Tome 1. 1800/1858 : Pascal CHOISY. Editions André RUPP. 16, avenue Robert Schuman 68100 MULHOUSE

- Contribution à l'étude de la poste en milieu rural dans le département du Nord : Paul STOPIN, 47 av. F. Mitterand 59494 PETITE FORET. 2000

- Les tarifs postaux français (Editions Brun et fils1989): ALEXANDRE, BARBEY, BRUN, DESARNAUD et JOANY (Editions Brun et fils 1989)

- Etre facteur dans le Nord (1830-1940) M. MARGUERIT, C. DA FONSECA. Comité pour l'Histoire de la Poste.

- Introduction à l'Histoire postale des origines à 1849.M. CHAUVET(Editions Brun et fils 2002)

- Introduction à l'Histoire postale de 1848 à 1878.M. CHAUVET(Editions Brun et fils 2002)

- Enquête postale de 1847. BNF Richelieu, Fond français 9787-10129.

- Instruction Générale sur le Service des Postes de 1832, Tomes 1,2,3. Réimpression société des amis du musée de la Poste.

- Instruction spéciale sur le service des Distributions de 1834. Réimpression société des amis du musée de la Poste.

- Instruction Générale sur le service des postes de 1856. BNF , Gallica.

- Instruction Générale sur le service des postes de 1868. BHPT(Paris) cote PB28

To explore French postal rates without necessarily having to consult postal regulations: les tarifs postaux français de Jean-Louis Bourgouin.