Ukrainians in the coal mines of the Nord 1942-1945

e postcard below depicts a little-known chapter of the Second World War in Northern France, highlighting the presence of Ukrainian workers in the mines of Nord-Pas-de-Calais.

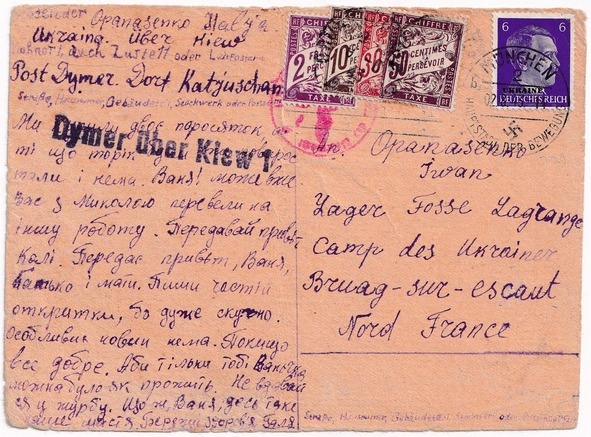

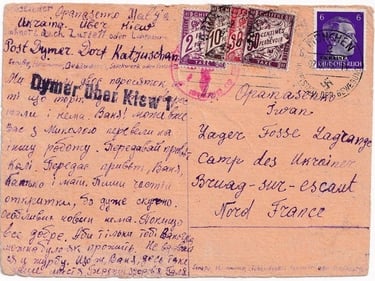

Card posted to DYMER (Ukraine) and addressed to a Ukrainian worker, Iwan Opanasenko, employed at the Fosse Lagrange (Coal mining company of ANZIN) in BRUAY-SUR-ESCAUT.

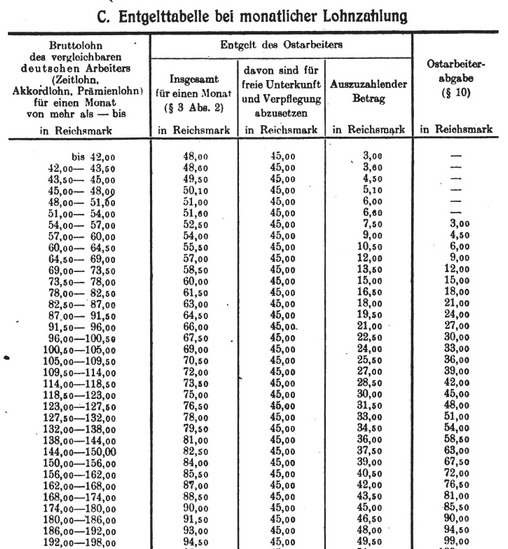

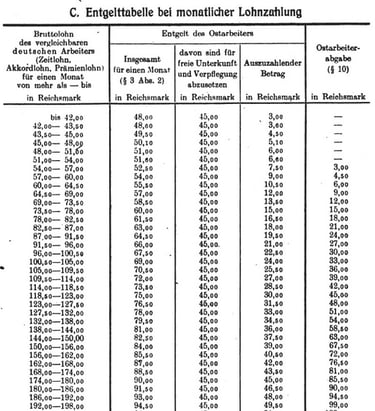

Extract from the salary scale of an Ostarbeiter in June 1942.

1st column: German reference monthly wage.

2nd column: Ostarbeiter's monthly wage.

3rd column: deduction for board and lodging.

4th column: payment made to the worker.

5th column: tax paid by the employer.

Source: Amtsblatt des Reichspostministerium 1942, page 536.

Postal examination took place in Berlin (censorship stamp beneath the French tax stamps), and the card passed through MUNICH on 2 August 1943. The required postage for France was 15 pfennigs. However, the BRUAY-SUR-ESCAUT post office applied a tax of 2F90, calculated as follows:

Double postage deficiency: 18 Pf

Exchange rate between the French and German letter tariffs: 4F/25Pf = 16. According to UPU regulations, this ratio is always based on the letter rate, even if the taxed item is not a letter. (French letter rate: 4F; German letter rate: 25 Pf).

Tax applied: 0.18 × 16 = 2F88, rounded up to 2F90.

Ukrainian workers.

Given that foreign workers brought to France at the time were generally employed in German services such as the Organisation Todt, one might wonder why a Ukrainian was working for a mining company in northern France.

To answer this question, we must examine the directives issued by the German authorities.

Several decrees were enacted regarding the voluntary or forced recruitment of foreign labour. However, the one specifically concerning Ukrainians dates from 20 February 1942. Commonly referred to as the "Ostarbeiter-Erlass" (Decree on Workers from the East), its official title was "Allgemeine Bestimmungen über Anwerbung und Einsatz von Arbeitskräften aus dem Osten" (General Provisions on the Recruitment and Use of Labour from the East).

The term "Ostarbeiter" did not apply to all workers from the occupied East but specifically to those from the occupied Soviet territories, except the Baltic states and the regions of Lemberg and Lviv. This decree permitted the recruitment of workers for employment in agriculture and industry, both in Germany and in Ukraine.

In Germany, wages were determined by the worker's qualifications, but for the same level of skill, an Ostarbeiter earned less than a German worker. Moreover, their wages were further reduced by deductions for accommodation and food. However, Ostarbeiter were covered by German health insurance.

In Germany, workers from the East were housed in closed, guarded camps, usually located within or near their workplace. To prevent employers from favouring foreign workers over German workers, they were required to pay a tax known as the "Ostarbeiter-Abgabe" (Tax on Workers from the East).

Finally, Eastern workers were required to wear a distinctive badge sewn onto the left side of their garment at chest level. This badge featured the word "OST" on a blue and white background.

Recruitment measures varied in their level of coercion. Some workers volunteered to go to Germany in an attempt to escape the extremely harsh living conditions in the occupied Soviet territories. However, the working conditions in Germany were far worse than had been portrayed during recruitment. News of these hardships quickly spread in Ukraine, leading to a sharp decline in the number of volunteers. As a result, the German authorities were forced to resort to compulsory recruitment.

From 25 November 1942, Ostarbeiter were required to use special postcards overprinted with the word "Ukraine" to communicate with their relatives. They were permitted to send only two postcards per month. The German domestic postal rate (6 Pf) applied. Mail was subject to censorship, with correspondence addressed to Ukraine inspected by the Auslandsbriefprüfstelle Berlin (Berlin Charlottenburg 2, Zoo), while mail bound for the rest of the occupied Soviet territories was controlled by the Auslandsbriefprüfstelle Königsberg 5.

Ukrainian Workers in the Mines of Nord and Pas-de-Calais.

From the beginning of the Occupation, coal production in the region’s two departments was lower than in 1939, as many miners were held in prisoner of war camps in Germany. Coal was vital not only for French domestic needs but also for the German war effort.

In May 1942, the Oberfeldkommandantur 670 in LILLE informed mining companies that the German authorities would be sending 3,000 Ukrainian workers at the end of May (although they did not actually arrive until July). This number was expected to increase to 10,000 [2].

Mining companies were not in favour of receiving these workers—some of whom were Soviet prisoners of war—as they preferred the return of French prisoner-of-war miners. Furthermore, the Ukrainian workers lacked the skills of professional miners. Lastly, bringing workers from Soviet republics into the coalfields, where the local population was strongly committed to communist ideas, was considered a risky move [3].

These workers had to be housed in camps. The construction and installation of these camps were partially funded by the German authorities using occupation funds. The Germans paid for the barracks, infirmary, kitchen, fencing, heating, and bedding, while the mining companies were responsible for crockery, cooking utensils, access roads, electricity, heating, and the costs of assembling the barracks and camp infrastructure [4].

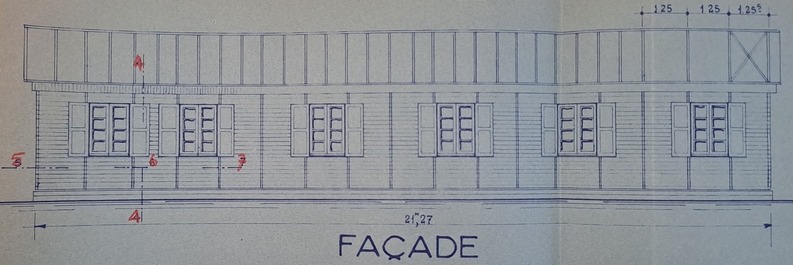

The Germans provided prefabricated barracks, each of which could accommodate 50 men.

The camps were initially guarded by Walloon guards (Rexists) until the end of 1943. After this, depending on the company, responsibility for worker surveillance was assigned to either French guards or German military police, who were accompanied by workers' representatives.

Upon arrival, workers from the East were issued with:

2 work jackets

2 pairs of trousers

2 shirts

2 towels

2 pairs of espadrilles

1 pair of clogs

1 helmet

1 water bottle

These workers were paid approximately 40% less than French miners. In addition to this wage disparity, mining companies deducted the costs of food and accommodation from their wages, while the German authorities imposed an additional tax.

For example, in November 1942, a worker earning a fortnightly wage of 1,020 francs received only 300 francs, as 390 francs were deducted for food and accommodation and 330 francs went towards the "Russian labour tax".

The German authorities instructed mining companies to ensure that workers from the East reached 50% of the productivity of French miners after two months, increasing to 70% after four months [5].

As feared by the mining companies, this workforce proved unsuited to mining, particularly underground work. A 16 March 1943 report from the DROCOURT mine [6] stated that, despite displaying general goodwill, a Ukrainian worker was 50% less productive than a French miner. Moreover, these workers required constant supervision and support from experienced French miners and had higher rates of absenteeism due to illness. The acclimatisation period was deemed too short and needed to be extended. Ultimately, the integration of Eastern European workers into underground mining reduced overall productivity.

To improve motivation, the German authorities instructed companies to provide recreational opportunities, including outdoor sports and indoor activities. A bonus system was introduced, offering extra cigarettes or food to the most productive workers.

Escapes and Reallocation of Labour.

There were many cases of escape among these workers.

From mid-1944, as Allied bombing campaigns over Nord and Pas-de-Calais intensified, the Oberfeldkommandantur ordered mining companies to reassign some Eastern workers and prisoners to repair railway lines or clear rubble.

Liberation and Repatriation.

Nord and Pas-de-Calais were liberated in early September 1944. The Ostarbeiter and prisoners of war employed in the mines were gradually released. From October 1944, the French authorities established assembly camps for Soviet citizens. On 10 November 1944, a Soviet repatriation mission was set up in PARIS under the authority of Major-General Dragun.

Upon liberation, the Ostarbeiter received a bonus, but their remaining wages were paid directly by the mining companies—either to Major Orianev for workers still present in the region or to Major-General Dragun for those who had already departed [7].

Most of these workers were repatriated to the USSR, with little choice in the matter. The Franco-Soviet agreement on the maintenance and repatriation of French and Soviet citizens, signed on 29 June 1945, stipulated in its protocol that:

“All Soviet and French citizens are subject to repatriation, including those who are being prosecuted for crimes committed in their country as well as on the territory of the other signatory country.”

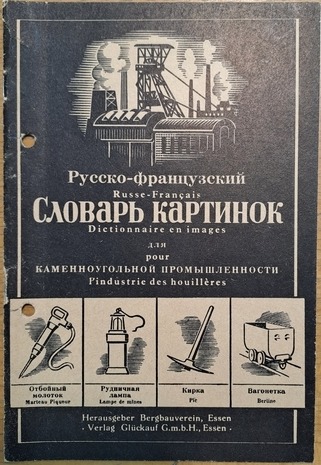

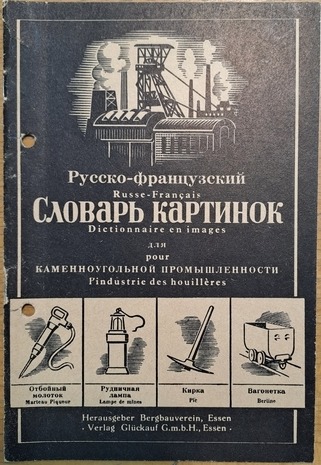

To reduce the language barrier and facilitate exchanges between workers, a dictionary of technical terms was published.

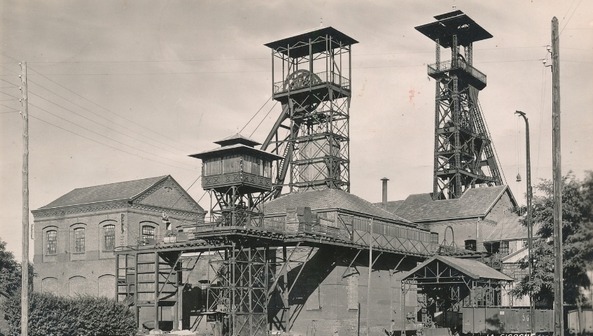

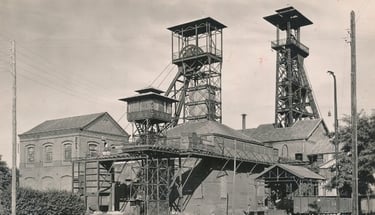

Ukrainian workers at the fosse Lagrange at BRUAY-SUR-ESCAUT.

The Ukrainians arrived in BRUAY in July 1942. In January 1944, 496 of them were working in the camp near the fosse Lagrange.

Fosse Lagrange at BRUAY-SUR-ESCAUT.

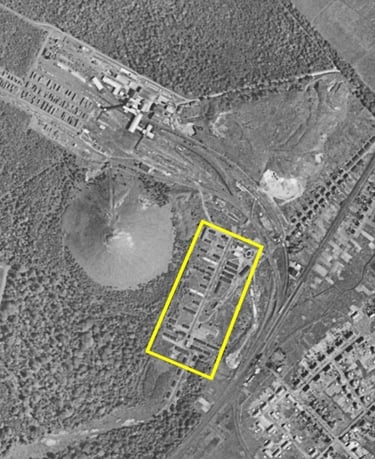

Aerial photo from the early 1950s showing the fosse Lagrange and what remains of the Ukrainian camp barracks (yellow rectangle).

We can learn some details about these workers from a police report written by Inspector Pruvost of the Renseignements Généraux (General Intelligence Service) at the VALENCIENNES police station [8].

The report states that the workers had been recruited from the KIEV region and were aged between 16 and 21. The postcard shown above was written in KATYUZHANKA, located north-east of KIEV.

These Ukrainian workers were assigned across the six pits of the ANZIN Mining Company. Although they were paid the same as French workers, their productivity was 25% lower than that of French miners. However, they enjoyed relative freedom, as they were allowed to leave the camp between 5pm and 8pm, as well as all day on Sundays.

The camp was guarded by an interpreter, 15 workers selected for their intelligence, and three Feldgendarmes.

At the time of the report, the Ukrainian workers appeared pleased with the German army’s setbacks in the USSR, although this sentiment seemed to stem more from patriotism than from support for the Bolshevik cause.

Concerns About Political Influence.

Inspector Pruvost concluded his report with the following assessment:

"It is to be feared that these workers may become a source of unrest in this sector of Bruay-sur-Escaut, where the population is largely sympathetic to Muscovite ideas [sic]. Furthermore, the workers' housing estates in the Thiers, Lagrange, and Sabatier pits are 90% Polish in the first two cases and 80% Spanish in the latter—both communities known for their strong ties to the Communist Party and the Iberian Anarchist Federation. It should also be remembered that Bruay-sur-Escaut and the surrounding area provided many volunteers for the International Brigades in Spain. It therefore seems that the prolonged presence of Russian workers in this region is not desirable."

The Case of Iwan Opanasenko.

To conclude this section, records indicate that Iwan Opanasenko was assigned service number 262 and received his liberation bonus on 25 October 1944. He was subsequently repatriated to Ukraine, as there is no further trace of him in the region.