19th Century French Postal Fraud

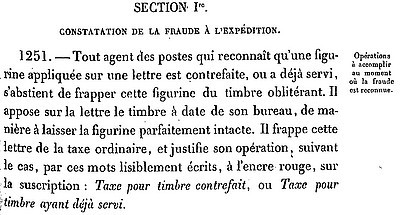

Since the introduction of the postage stamp and throughout the 19th century, the Post Office remained vigilant against the risk of stamp reuse. At the time, the Post Office operated under the authority of the Ministry of Finance, meaning postal fraud could result in significant revenue losses for the State. To combat this issue, authorities implemented various technical measures—such as stamp cancellation methods and specialized printing inks—as well as legal deterrents, since postal fraud was classified as a criminal offence.

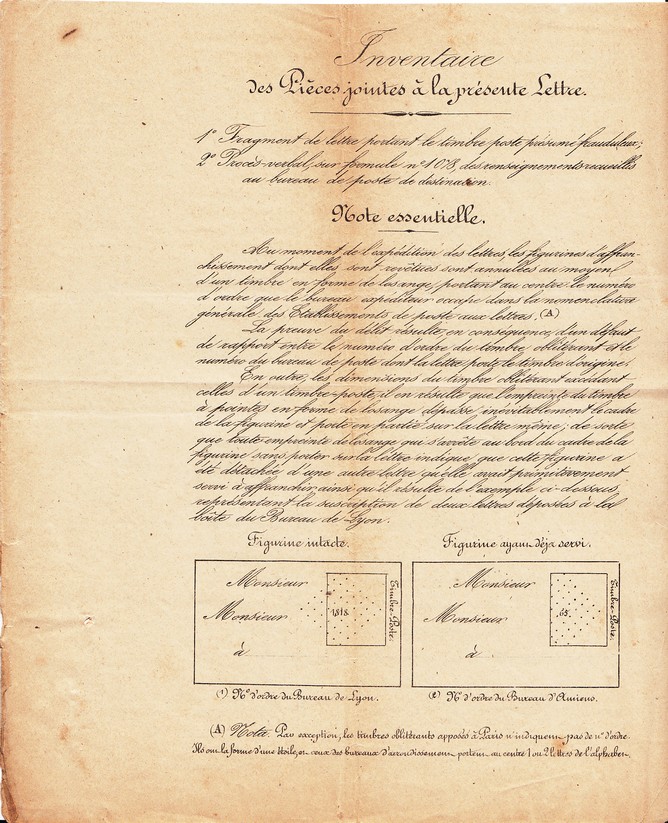

Numeral cancels played a crucial role in detecting reused stamps. It was relatively easy to verify whether the date stamp from the originating post office corresponded with the numeral cancel, helping to identify fraudulent reuse.

Anyone caught reusing a cancelled postage stamp faced prosecution in a criminal court.

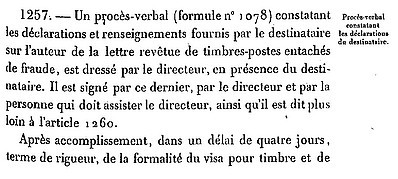

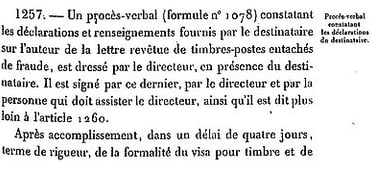

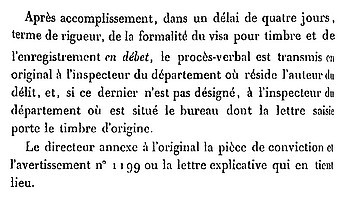

To contextualize the following documents, I have included articles from the 1856 General Instruction on Postal Services, a manual that served as the definitive reference for postal agents at the time.

The file does not include the sealed envelope (model 1198), which is expected, as it was only intended for temporary retention.

At the same time, a Notice of Issue for a letter bearing a presumed fraudulent postage stamp (model 1197) was sent in duplicate—one copy to the Administration in PARIS and the other to the Departmental Postal Inspector in LILLE.

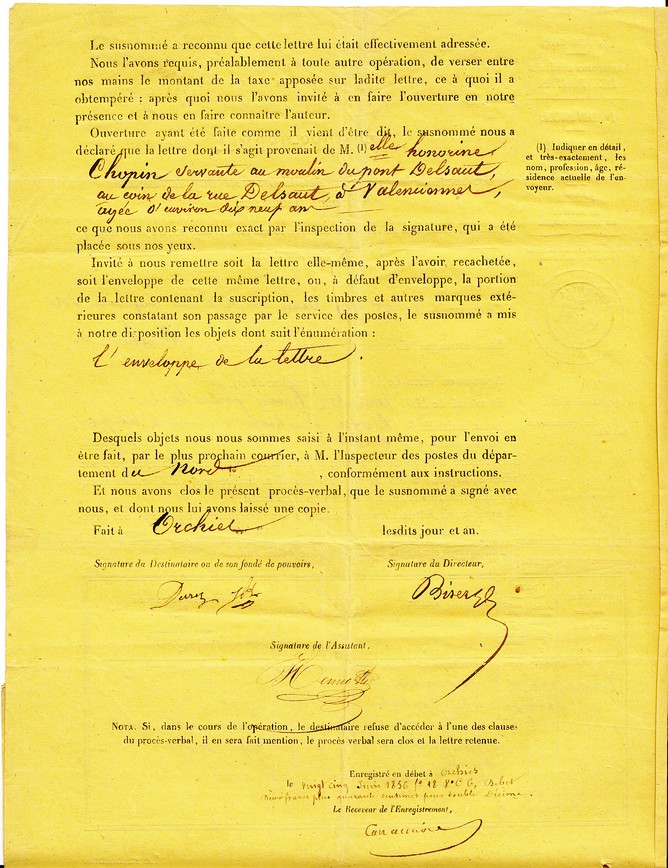

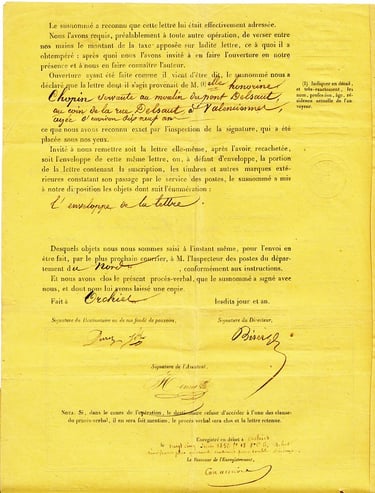

In ORCHIES, the sealed envelope was received with all the precautions required by procedure.

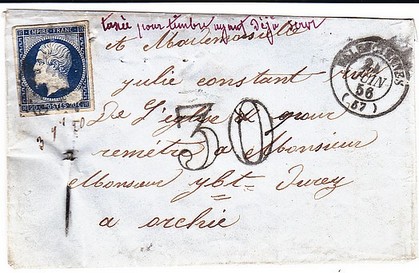

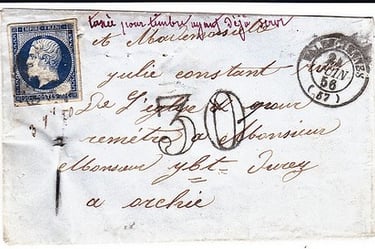

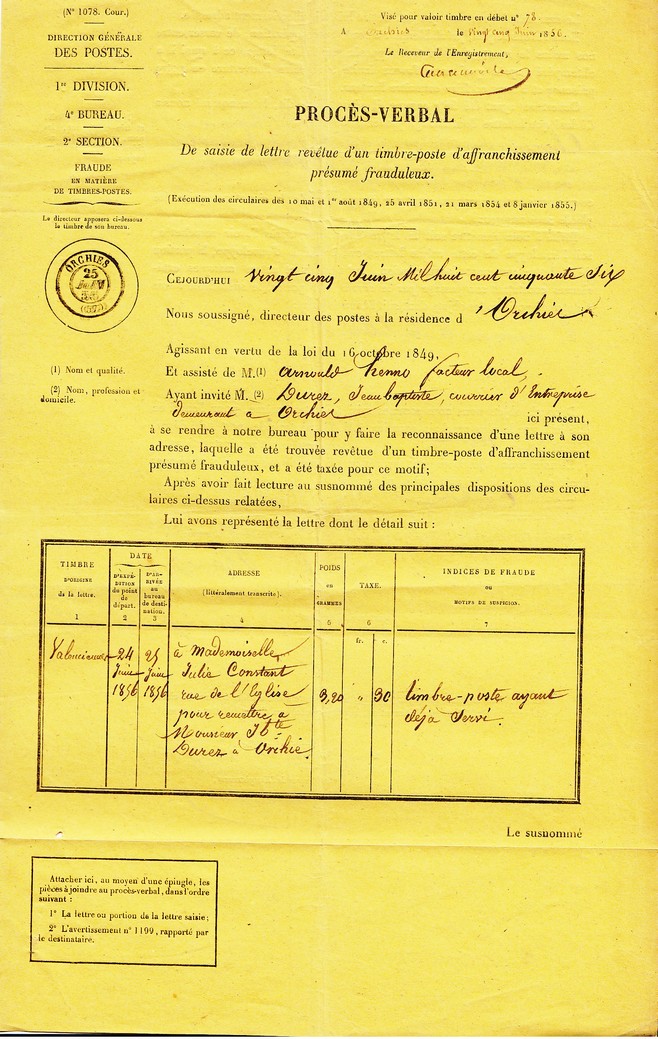

Letter from VALENCIENNES to ORCHIES, dated 24 June 1856.

Upon inspection, the postal workers in VALENCIENNES noticed that the stamp bore traces of a previous cancellation. As a result, they marked it "taxée pour timbre ayant déjà servi" ("taxed for stamp already used"). The letter was subsequently treated as unfranked and taxed accordingly.

The letter was sent in a sealed envelope to the ORCHIES post office.

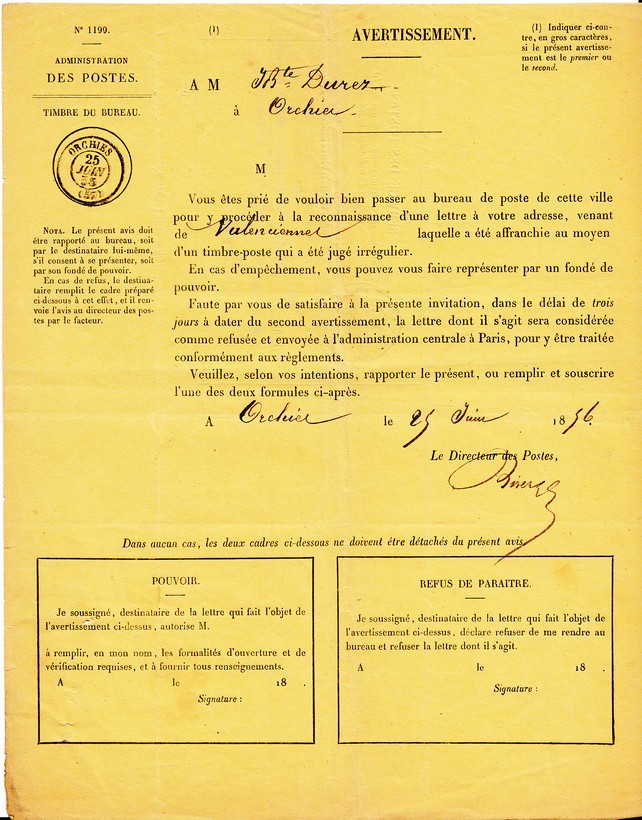

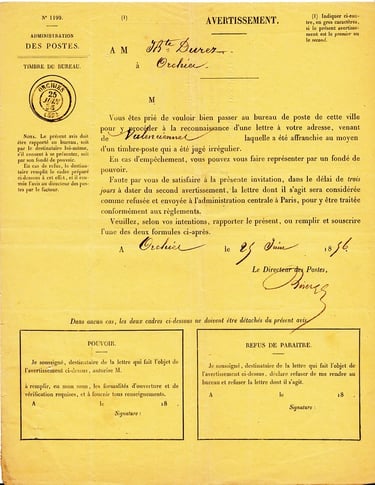

In this case, we are in a rather special situation, as we are dealing with a letter addressed to one person to be delivered to another. The Post Office has nevertheless taken this into account.

Mr Durez, a company courier by profession, agreed to come to the post office that very day. At the post office, he was expected to fill in a report.

The minutes were signed by the Director, the addressee (or their representative), and an assistant. This assistant was required to be sworn in and, in all cases, had to be a member of the Postal Administration.

The minutes also reveal that the sender of the letter, Honorine Chopin, resided in VALENCIENNES.

The documents in the file were then forwarded to the postal inspector of the department where the letter originated.

This marks the conclusion of the postal procedure and the beginning of the criminal process.

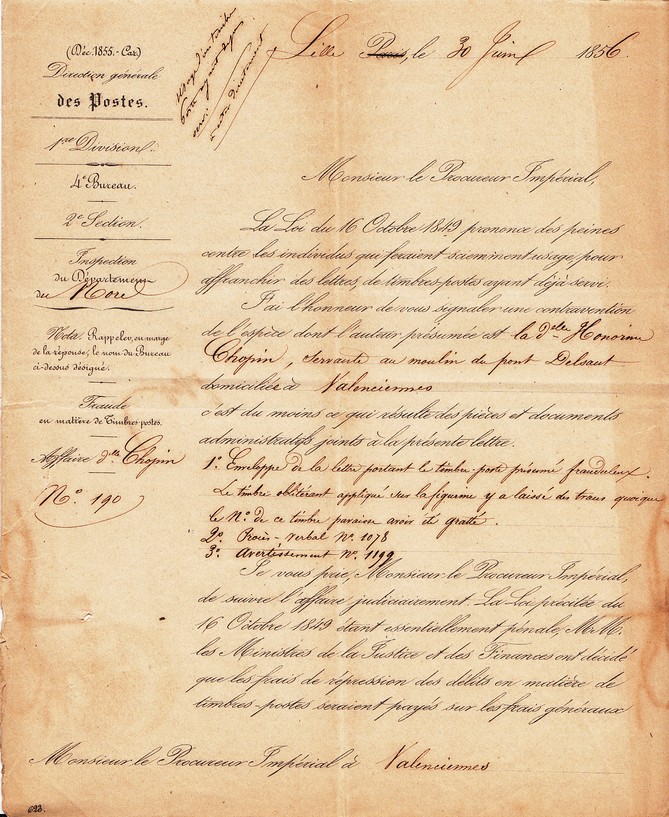

Through the Departmental Postal Inspector, the Administration will file a complaint with the Imperial Prosecutor of the District of VALENCIENNES, to which VALENCIENNES belongs.

This complaint has been submitted using the attached document.

Honorine Chopin was summoned and questioned at the VALENCIENNES police station on 4 July 1856. She admitted to writing the letter and affixing the postage stamp but denied knowingly using a previously cancelled stamp. She stated:

"[...] but this stamp could not have been cancelled. I had bought it along with several others, which I kept in my trunk. This was the last one I had left. I admit that I accidentally stepped on it one day while taking some papers out of my suitcase, and it fell on the floor [...]".

A month after the letter was sent, Honorine Chopin appeared before the Valenciennes Magistrates' Court. She was found guilty of using a previously used postage stamp and was sentenced to pay a fine of 7.25 francs, along with legal costs.

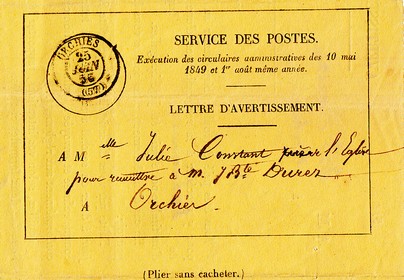

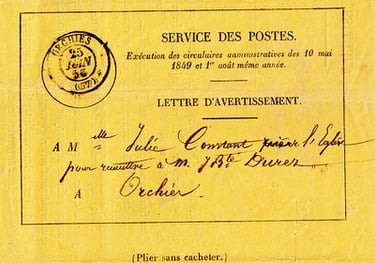

A notification letter was sent to the addressee on 25 June, inviting them to visit the post office to identify the letter. The secrecy of correspondence was considered sacred, and the Post Office was not permitted to open letters except under specific conditions.

Furthermore, this was merely an invitation, not a summons.