Feldpost 1914-1918

Practice

The flow of mail varied depending on whether it was travelling from the front to Germany or vice versa.

From Germany to the Front.

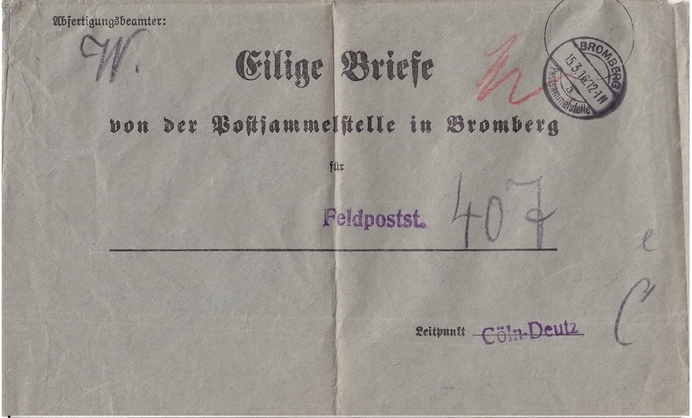

Mail destined for the military was collected at collection depots (Postsammelstellen), which were responsible for sorting the mail. Each military post office handled the sorting and bagging of mail, with every unit being attached to a specific military post office.

The mailbags were then transported to the Leitpunkte, advance depots situated near the border but still within German territory. Each army had its own depot, although multiple armies could share the same one. These depots were the only locations that held precise information about the positions of units and their corresponding post offices. To manage this, they used a directory known as the Field Post Index (Feldpostübersicht), which detailed the links between units and post offices. This index was constantly updated with information from the army post offices and, more importantly, from headquarters, which alone had knowledge of changes in unit locations.

The Leitpunkte were responsible for sorting mailbags from the collection depots and distributing them to the army post offices. Whenever possible, entire wagons were packed exclusively with mailbags destined for the same army post office. The largest advance depot for the Western Front was located in warehouses near Cologne station.

Up to this point, the civilian postal service handled the routing of mail.

Once sorted, the wagons were dispatched to the transhipment centres (Postumschlagstellen), located either in Belgium or at army stop points along the line, sometimes at the terminus. Each army had multiple transhipment centres, to which its units were assigned.

Beyond German territory, the military post office took over the handling of mail, making it subject to the uncertainties of war.

Upon arrival at a transhipment centre, mailbags were retrieved by staff from each military post office and subsequently distributed to soldiers.

Senders needed to ensure that they addressed letters with absolute accuracy. Otherwise, mail could be lost, delayed, or returned. Addresses were not to include location details alongside the recipient’s unit name.

Dispatch envelope containing mail sent by the Postsammelstelle in BROMBERG to Feldpoststation no. 407 in VALENCIENNES.

From the Front to Germany.

Soldiers’ mail was collected within their company, with an officer and, later, a postal control office randomly inspecting certain letters or postcards. This examination ensured that no concealed military information was present and that the sender’s location was not disclosed.

From there, the mail was sent to the field post office serving the unit. In the trenches, letterboxes were installed to facilitate mail collection.

At the field post office, the mail underwent an initial rough sorting, primarily by major towns.

The postal bags were then transported to the distribution centres (Postverteilungstellen), where the mail was sorted again, this time by province or state. Mail from large towns was processed separately.

Next, the mailbags were forwarded to the sorting centres (Sortierstellen) of the respective provinces or states.

Mail sent from a soldier in one army to a soldier in another army did not follow the same route.

At the start of the conflict, direct mail exchanges between two different armies were not possible. Instead, mail had to be sent first to a collection depot (Postsammelstelle) in Germany before being redirected to the recipient’s army. This system inevitably caused significant delays.

In October 1914, Joint Exchange Centres (Heeresbriefstellen) were established to improve efficiency. These centres were responsible for collecting, sorting, and forwarding mail between different armies. They were typically located in rear areas.

Postal Rates.

As in many countries, German troops in the field benefited from unlimited free postage for personal correspondence.

The Post Office distinguished between private and non-private mail. While private correspondence was exempt from postal charges, non-private correspondence was not.

Postcards, an ideal means of communication, were free for personal use. However, if they were not of a private nature, they incurred a fee:

5 Pfennig until 31 July 1916,

7.5 Pfennig until 30 September 1918,

10 Pfennig from 1 October 1918.

Private letters were free up to 50g. Beyond this weight, postage was 20 Pfennig, but from 5 October 1914, the rate was reduced to 10 Pfennig. Letters were accepted up to 250g.

From the end of December 1916, letters weighing between 250g and 500g were permitted. The postage for these heavier letters was 20 Pfennig for private correspondence.

Since there were no weight increments beyond 500g, the Post Office allowed a 10% weight overrun without additional charges. This meant:

A letter weighing between 50g and 275g cost 10 Pfennig,

A letter weighing between 275g and 550g cost 20 Pfennig.

The Germans referred to heavy letters as "Päckchen" (small packets).

For single non-private letter:

Up to 20g: 10 Pfennig until 31 July 1916, then 15 Pfennig until 1919

Up to 250g: 10 Pfennig until 31 July 1916, then 25 Pfennig until 1919

Mail with insufficient postage from the front to Germany was taxed at the rate of the insufficient postage. Letters with insufficient postage from Germany to the front were returned to the sender.

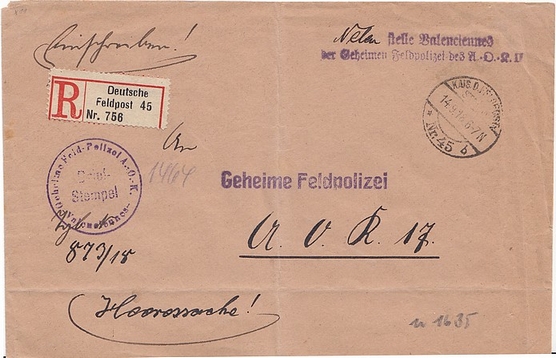

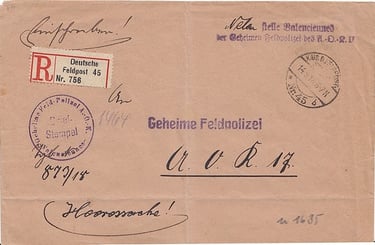

Letters were only registered for military service mail (Heeressache).

Free military registered letter posted at Feldpoststation no. 45 in VALENCIENNES. This is a service letter between the local branch of the 2nd Army's Secret Military Police (Geheime Feldpolizei, A.O.K 2.) and the 17th Army's High Command (A.O.K 17). The letter was posted on 14 September 1918. The date stamp is not dumb or filed, as it is a registered letter. The High Command of the 17th Army had been in DENAIN since 1st May. We are here in the last days of the presence of the Feldpoststation no. 45 in VALENCIENNES, since this town will be part of the 17th Army zone in September 1918.

Soldiers could take advantage of declared-value letters, which provided additional security for valuable correspondence.

Letters up to 50g and valued up to 150 Marks were free.

Letters over 50g and valued up to 300 Marks cost 20 Pfennig.

Letters over 50g and valued between 300 and 1,500 Marks cost 40 Pfennig.

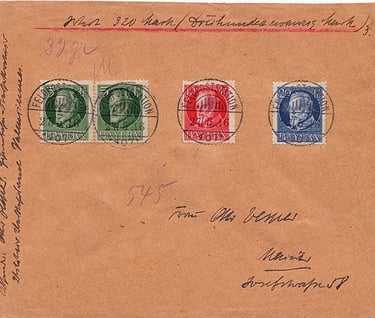

This letter was posted at the Bavarian Feldpoststation no. 407 (VALENCIENNES station). It contained 320 Mark and weighed 32 g. Postage for this type of letter was 40 Pf (under 50 g, over 300 Mark). The registration number of this letter is 545.

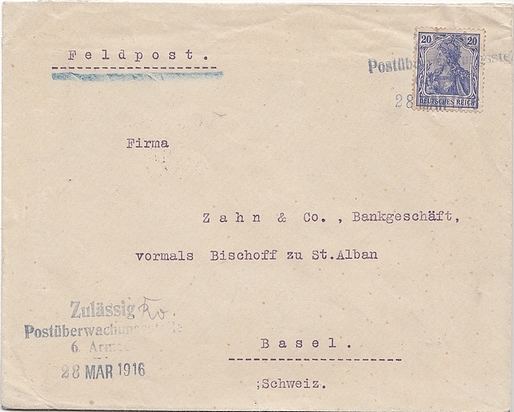

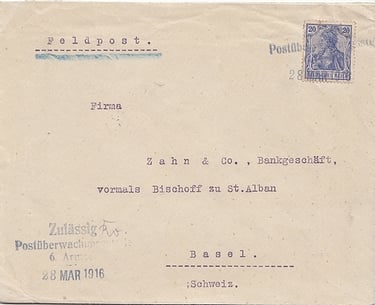

From certain dates, postcards, and letters weighing up to 50g sent to specific neutral countries were exempt from postage, provided that soldiers could prove a close family relationship with the recipient (wife, parents, grandparents, children, brothers, or sisters). Letters had to be posted open.

Switzerland: Since 8 October 1914

Spain: Since 15 February 1915

Uruguay: From 13 March 1915 to 7 October 1917 (when Uruguay entered the war)

Denmark: Since 9 April 1915

Postal Interruptions.

In preparation for major offensives and to maintain secrecy, the High Command could impose a postal break, lasting anywhere from a few days to several weeks. During these interruptions, soldiers were strictly forbidden from carrying mail into the trenches. If a soldier were captured in a coup de main (a sudden enemy raid) before the attack, any seized mail could reveal critical details about the impending offensive.

These postal interruptions could be either geographically restricted, affecting only units in a specific sector of the front, or targeted at units in transit, particularly those preparing to take part in the offensive.

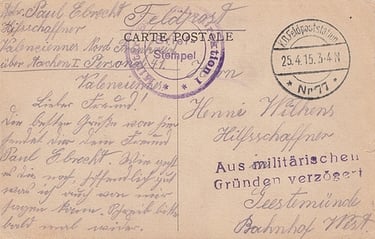

Since postal suspensions were never publicly announced, soldiers and their families often blamed the Field Post for the delays, unaware that the Field Post itself was also affected by these restrictions. As a general rule, field post offices marked delayed mail with the stamp "Auf militärischen Gründen verzögert" (delayed for military reasons).

However, the effectiveness of postal interruptions was limited. Soldiers often found ways to bypass restrictions. A common method was entrusting their letters to leave-holders—comrades returning to Germany or another unaffected area—who would then post the mail outside the restricted zone.

Even General Erich Ludendorff, in his memoirs, acknowledged the limitations of postal suspensions, stating:

"Postal interruptions were of no value. There were too many channels of information to the country. I couldn’t suspend leave because it was the only thing the High Command could give the soldier."

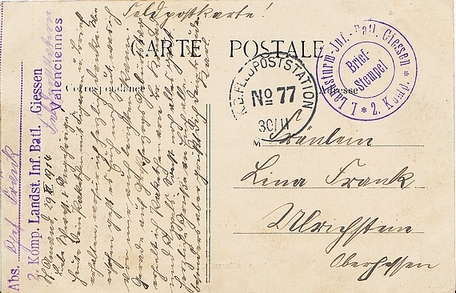

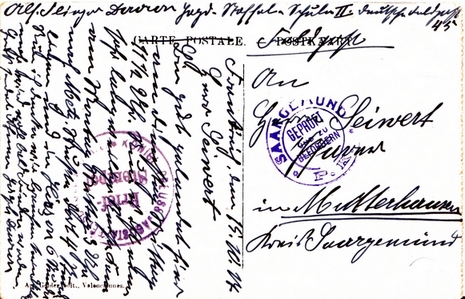

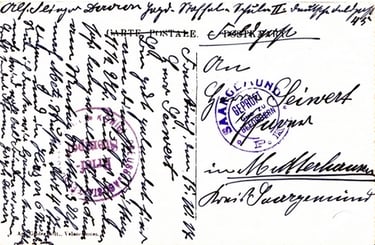

This card was sent by an auxiliary railway clerk (Hilfsschaffner) who was employed by the Military Railways Directorate No. 1 (Militär-Eisenbahndirektion I.). In April 1915, the mail handled by Feldpoststation no. 77 in VALENCIENNES was subject to a postal interruption.

Postal control.

In addition to the delays imposed on soldiers' mail, the German army—like many other European armies—practised postal control. However, this oversight was not conducted by the army post office itself but by military departments entirely separate from the postal service.

From the beginning of the war until April 1916, the control of soldiers' correspondence was unregulated, leading to highly arbitrary enforcement within units. The individuals responsible for inspecting the mail—usually officers—had no specialised training in postal censorship, which resulted in inconsistent practices:

Some company commanders focused solely on detecting military secrets.

Others scrutinised soldiers' private lives, looking for inappropriate or suspicious content.

Some were reluctant to carry out such checks at all.

This lack of regulation created significant disparities in how postal control was conducted across different units.

This letter to Switzerland was sent as military mail (marked Feldpost) and was franked at the international rate of 20 Pf. As it was not private mail, since it was addressed to a banker, it could not circulate postage-free. Censored on 28 March 1916 by the 6th Army's postal control centre in VALENCIENNES, the letter arrived in BASEL on 2 April 1916. Censor mark: Zulässig Postüberwachungsstelle 6. Armee.

Citizens of Alsace-Lorraine, part of the Reichsland (imperial territory), were subject to even stricter postal censorship due to lingering doubts about their loyalty to Germany.

As early as 27 March 1914, the Ministry of War issued a secret decree that imposed restrictions on mail in the territories of Alsace-Lorraine and Baden (specifically under Strasbourg and Neuf-Brisach). The decree stipulated that, in the event of an imminent war or mobilisation, all:

Private correspondence had to be sent using postcards,

Business mail had to be sent in open envelopes to allow for easier inspection.

On 20 March 1917, the Ministry of War issued another decree, significantly increasing postal surveillance. Previously, only around 5% of mail was randomly checked; the new directive raised this to 90% of all correspondence. This drastic measure was justified by concerns over the Entente’s "systematic and increasing agitation" of the Alsace-Lorraine population.

The above card was written by an airman (Flieger) in training at Jagdstaffelschule II (Fighter School No. 2) near VALENCIENNES at LA SENTINELLE, which had been established on 8 August 1917. This card is bound for MOUTERHOUSE near SARREGUEMINES (Sarregemünd) in Moselle. It passed through the town's postal control centre, which stamped it "SARREGEMUND P.K. GEPRÜPFT UND ZU BEFÖRDERN" (Sarreguemines Postal Control Checked and to be dispatched). The card did circulate uncovered, otherwise the postal control stamp would not be there.

Postal Control Centres in the Valenciennes District.

Three postal control centres (Postüberwachungsstellen) were established in the Valenciennes district to monitor military and civilian mail. These centres operated under different army commands and were periodically relocated.

1. Postüberwachungsstelle of the 6th Army

Initially part of the Lines of Communication of the 6th Army (Etappenbereich der 6. Armee) from March 1915.

Transferred to the High Command of the 6th Army (Oberkommando der 6. Armee) in March 1916.

Based in Valenciennes until 30 September 1916, then moved to Tournai.

Renamed Postüberwachungsstelle No. 40 (P.Ü.St. 40) in February 1917.

2. Postüberwachungsstelle of the 1st Army

Operated under the 1st Army.

Located in Valenciennes from 1 October 1916 to 18 April 1917.

Renamed Postüberwachungsstelle No. 36 (P.Ü.St. 36) in February 1917.

Also referred to as "militärische Überwachungsstelle des Post- und Güterverkehrs der 1. Armee" (Military Post and Goods Control Centre of the 1st Army).

Moved from Valenciennes to Charleville on 18 April 1917.

3. Postüberwachungsstelle No. 39 (P.Ü.St. 39) – 2nd Army

Initially based in Saint-Quentin until early 1917.

Moved to Maubeuge, then to Valenciennes in April 1917, where it remained until at least 30 September 1918.

Expansion of Postal Control Centres.

From February 1917 until the end of the war, a total of nine postal control centres operated along the Western Front, including the Valenciennes centre.

P.Ü.St. 26a: METZ, Armeeabteilung C.

P.Ü.St. 26b: CONFLANS-VALLEROY, Armeeabteilung C.

P.Ü.St. 28: SEDAN, 3rd Army.

P.Ü.St. 30: VERVINS, LAON, 7th Army.

P.Ü.St. 31: MONS, 6ème, puis 17th Army.

P.Ü.St. 33: GAND, 4th Army.

P.Ü.St. 38: VIRTON, 5th Army.

P.Ü.St. 44: MAUBEUGE, since January 1918, for the 18th Army.

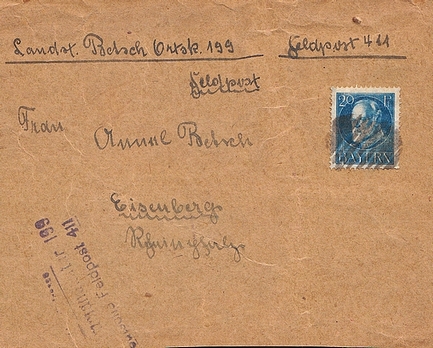

Card sent by a Territorial soldier (Landsturm). Feldpoststation no. 77 was at VALENCIENNES until June 1915.

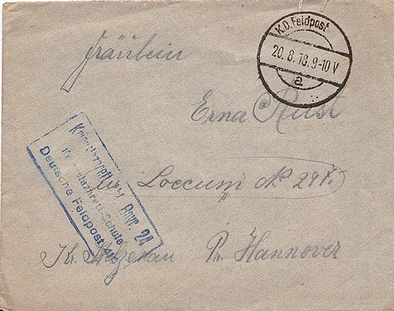

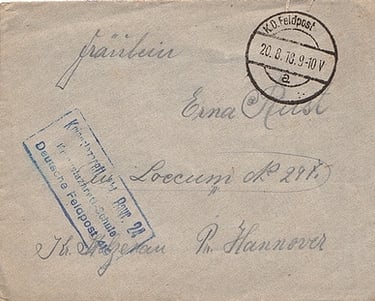

Letter sent by a soldier undergoing treatment at Bavarian military hospital no. 24. This hospital was located in the Ecole Pratique de Commerce et d'Industrie in DENAIN. This letter was handled by the Bavarian Feldpoststation no. 419, whose filed date stamp can be seen.

Fragment of a heavy letter from the front to Germany franked at 20 Pf for a weight of up to 550 g. This letter was processed by the Bavarian Feldpoststation no. 411 of ST AMAND.

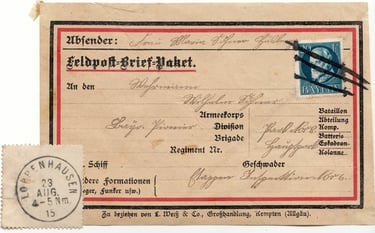

Label for a heavy letter from Germany to the front franked at 20 Pf for a weight of up to 550 g.

Need to find out more?

The occupation and liberation of Valenciennes are covered in 2 excellent works written a long time ago and now unfortunately out of print:

- Valenciennes, occupation allemande 1914-1918 (2 tomes) René DELAME. 1933.

- Valenciennes 10 octobre 1918-11 novembre 1918, l'évacuation, le bombardement, la délivrance J. THIROUX. 1920.

If you are interested in the subject of German Military Mail during the 1st World War and have no knowledge of German, you will need a good dictionary, as there are no works in French.

In any case, I recommend the following books:

- Geschichte der deutschen Feldpost im Kriege 1914/18 (Histoire de la Poste militaire durant la guerre 14/18) Karl SCHRACKE.

- Die deutsche Feldpost im Ersten Weltkrieg 1914-1918. (La poste militaire allemande pendant la première guerre mondiale 1914-1918) ANDERSON, BORLINGHAUS and KOOP.

- Stempelhandbuch der Deutschen Feldpost im Ersten Weltkrieg 1914-1918 Horst BORLINGHAUS.(2006).

- Die deutschen Feldpoststempel 1914-1918 Karl Heinz SCHRIEVER.

- La poste militaire allemande dans les territoires français occupés 1914-1918. L'arrondissement de Valenciennes. Emmanuel LEBECQUE. Feuilles marcophiles, 2016

As far as slightly more specialised works are concerned, in which you will find information on the posmarks of the units and the places of use. I recommend the following:

- Die Armee-Postdirektion 6 im ersten Weltkrieg 1914-1918 Burkhard KOOP. 2008

- Die Armee-Postdirektion 6 während des ersten Weltkrieges B. KOOP. 2010

- Handbuch und Katalog der deutschen Fliegertruppe im 1. Weltkrieg 1914-1914. H. BORLINGHAUS.

- Les Estampilles Postales de la Grande Guerre. Stéphane STROWSKI. Editions Yvert et Thellier 1976.

- Die Post im Westlichen Etappengebiet und ihre Abstempelungen. E. HEBERLE. 1928.

- Die Deutsche Heerespost an der Westfront. K. ZIRKENBACH 1935-1936.

- Le courrier civil dans le Nord de la france occupée 1914-1918. Gerhard LUDWIG, André Van DOOREN. 2018

Some works on the German armies and their orders of battle during the war may be useful. After 15 February 1917, date stamps no longer mentioned divisions and only regimental stamps or handwritten entries by soldiers gave us information about divisions and their military post office. However, how can we tell from this fragmentary information whether or not a unit belonged to a particular division? The German archives on this subject are practically non-existent (destroyed by bombing during the 2nd World War). However, a great deal of information can be found in 2 books:

- Histories of the 251 division of the German army which patricipated in the war 1914-1918. LONDON STAMP EXCHANGE LTD. 1989.

- German Divisions in World War I (Volume 1 to 7) de Dirk ROTTGARDT. Nafziger Collection.