Inscription of tax figures

In France, the indication of postal taxes on postage due or underpaid letters followed precise rules. These governed both the ink color and the design of the numerals, sometimes making them difficult to decipher for the untrained eye.

Units of Weight and Distance.

The postage cost of a letter depended on both its weight and the distance travelled between the origin and destination post offices.

Weight: Expressed in ounces and fractions of an ounce until the rate of March 22, 1800, when the gram became the definitive unit.

Distance: Initially calculated in leagues. The metric system, established as early as 1793 and confirmed by the law of 19 Frimaire, Year XIII (December 10, 1799), led the postal service to adopt kilometers with the rate of September 23, 1800.

The law of 3 Nivôse, Year VI (December 23, 1797) fixed the league at 5 km (2,566 toises), while previously the "poste league" was equivalent to approximately 3.898 km. The method of calculating postage thus varied over time, complicating retrospective analysis:

Postal routes (relay routes) were different from modern roads.

The postal service defined the official routes.

The value of the league changed in 1797, from 3.898 km to 5 km.

The rate of January 1, 1792 was an exception: distances were calculated from a department’s central point to another’s. Within the same department, postage was fixed. This method was abandoned with the rate of 1 Germinal, Year VIII (March 22, 1800), returning to calculation from post office to post office “by the shortest route according to postal service.”

All provisions of this rate could only be implemented with the rate of 1 Vendémiaire, Year IX (September 23, 1800). This practice continued until the rate of January 1, 1828, when distances again were calculated office-to-office but in a straight line. The rate of January 1, 1849 abolished the use of distance in postage calculation.

Currency.

Until the rates of 1 Germinal, Year VIII and 1 Vendémiaire, Year IX, postal charges were expressed in sols (sous). From these dates onward, postal taxes were calculated in décimes and francs (1 décime = 10 centimes). A particular case existed in provinces annexed by France under the Treaty of Aachen (1668), notably Hainaut and Flanders, where the "patar" currency was used—this system disappeared with the rate of January 1, 1792.

Ink Color.

Traditionally, taxes were written in black ink, although no explicit regulation mandated this in the General Instructions of 1792 and 1810. However, by the deliberation of the Postal Council of July 25, 1822 (article 8), it was decided that from October 1, 1822, “all letters born in Paris destined for the departments, arriving from departments, or passing through Paris will be taxed in azure blue ink in order to distinguish them entirely from departmental correspondences between themselves.”

It was only in the General Instruction of 1832 (article 222) that this rule was codified: “The tax and weight of letters and samples must be expressed in black ink in all offices, except in Paris where the tax on insufficiently prepaid letters will be written in azure blue ink.”

The blue ink would gradually disappear in favour of black. Starting from March 14, 1836 (Circular No. 62), letters passing through PARIS were taxed by the originating post offices, therefore in black. Although no regulatory text has been found on the matter, around 1849 PARIS stopped taxing letters to the departments in blue.

Numeral Format.

Before the Revolution, there were no regulations regarding the handwriting of tax numerals. Each office had its own style, which explains the diversity seen on historical letters. Only after 1792 did gradual standardization begin.

Thus, the 1832 Instruction does not mark the beginning of a standardization, but rather its culmination: it formalized a practice that had gradually become established in post offices over the preceding decades.

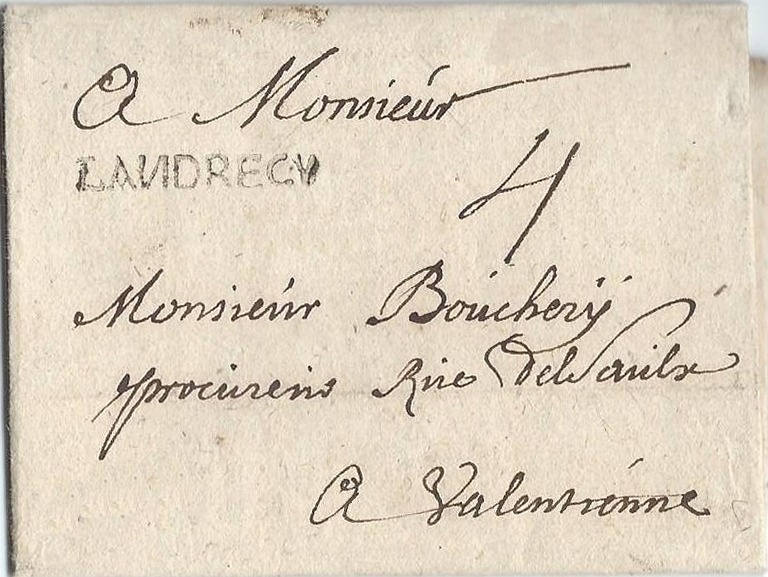

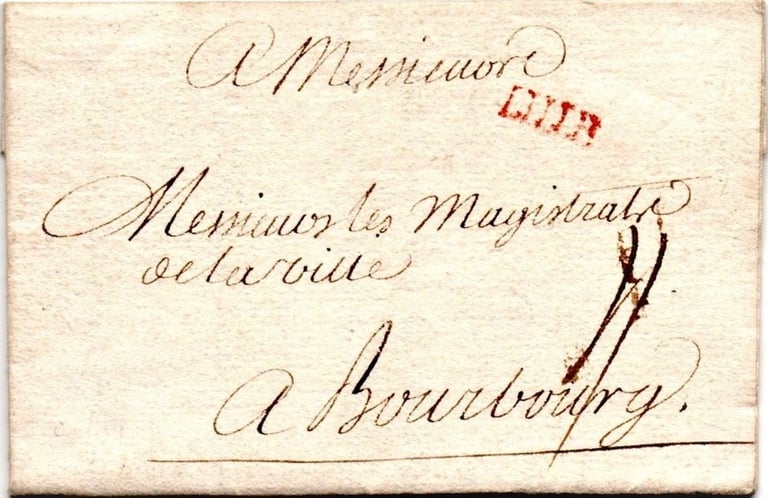

What happened over time with the numeral 4 (examples above) can also be observed with other numerals.

The first General Instruction on the postal service, issued in 1792, addressed the question of the form of tax numerals, but in rather vague terms: speaking of the post office director, Article III stated: 'He shall take care to clearly form the digits of his tax and shall avoid placing them over the names of the persons to whom the letters or packets are addressed.'

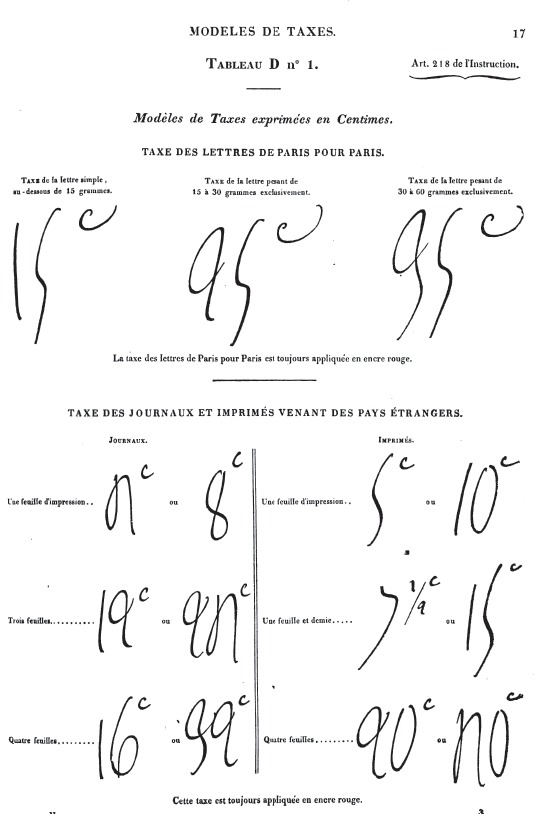

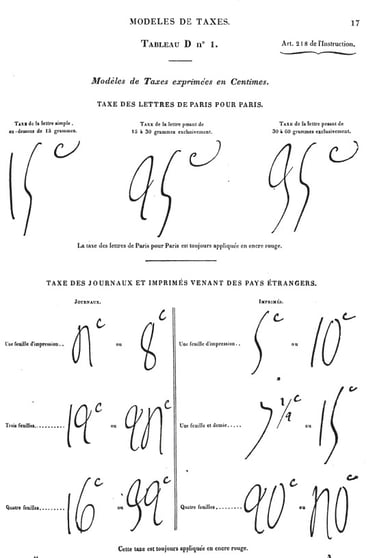

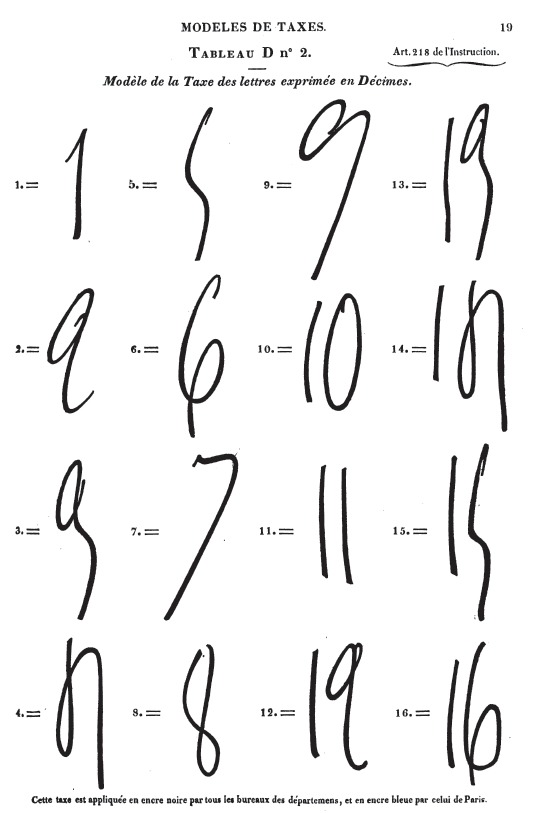

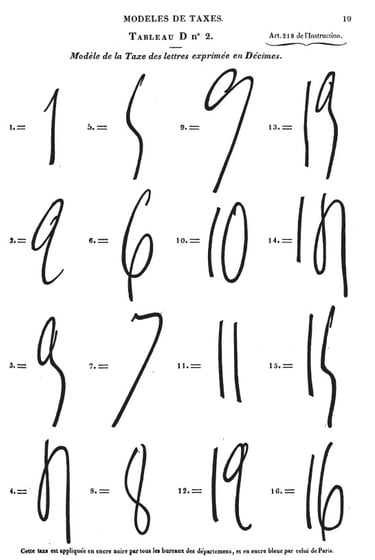

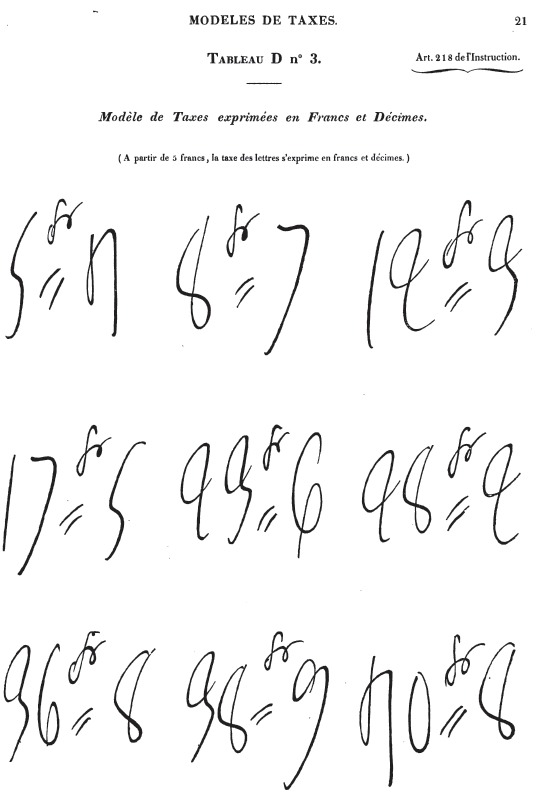

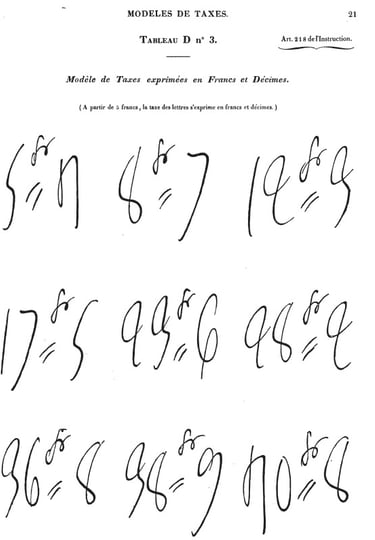

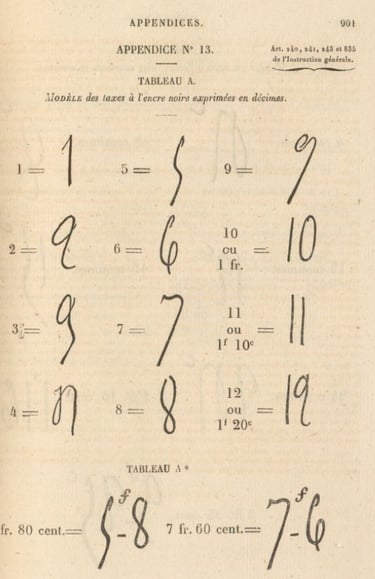

The General Instruction of 1808 repeated exactly the same wording in Article 109. It was not until the General Instruction of 1832 that the formalism of tax numerals was explicitly established and illustrated in Article 218: 'The figures indicating the tax must be formed according to the models shown in Tables D No. 1, D No. 2 and D No. 3 (see these tables, in Volume 2). These figures are placed on the address of the letter when the tax is to be collected at the destination, and on the back of the letter when it is prepaid.'

In 1717, a letter from LANDRECIES to VALENCIENNES was taxed at 4 patars, according to the rate of January 1, 1704 (for a letter with cover up to 20 leagues in distance).

1748, letter from LILLE to BOURBOURG taxed at 4 sols. Rate of January 1, 1704 (letter with cover up to 20 leagues in distance).

Table D 1, General Instruction, 1832. Taxes in centimes.

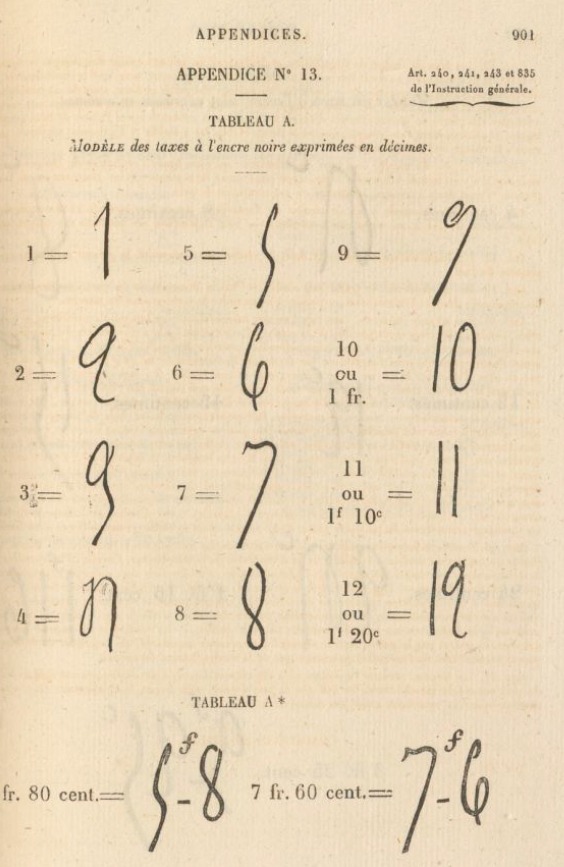

Table D 2, General Instruction, 1832. Taxes in décimes.

The subsequent General Instructions (1856, 1868, and 1876) all adopted the same numeral design.

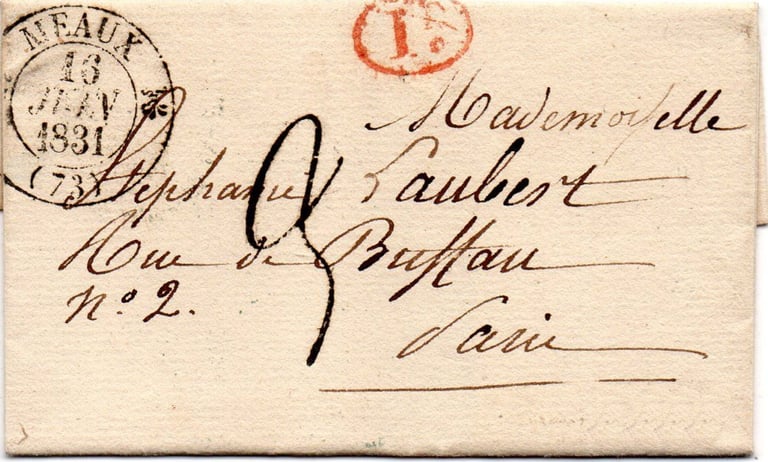

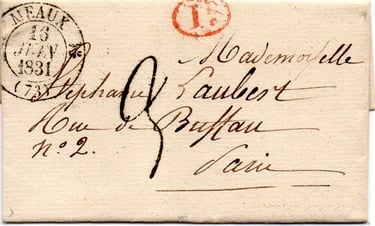

Postage-due letter weighing less than 7.5 g from a rural commune under MEAUX (rural décime) and taxed at 3 décimes for PARIS. Although used in 1831, the '3' tax handstamp is identical to that prescribed in the General Instruction of 1832.

The manual taxation of letters, whether handwritten or by handstamp, came to an end on October 1, 1882 (Monthly Bulletin No. 12 of September 1882): ‘The generalisation, from October 1, 1882, of the use of postage due stamps for the taxation of unpaid correspondence henceforth makes unnecessary the tax stamps or handstamps that had until now been supplied to postmasters ".

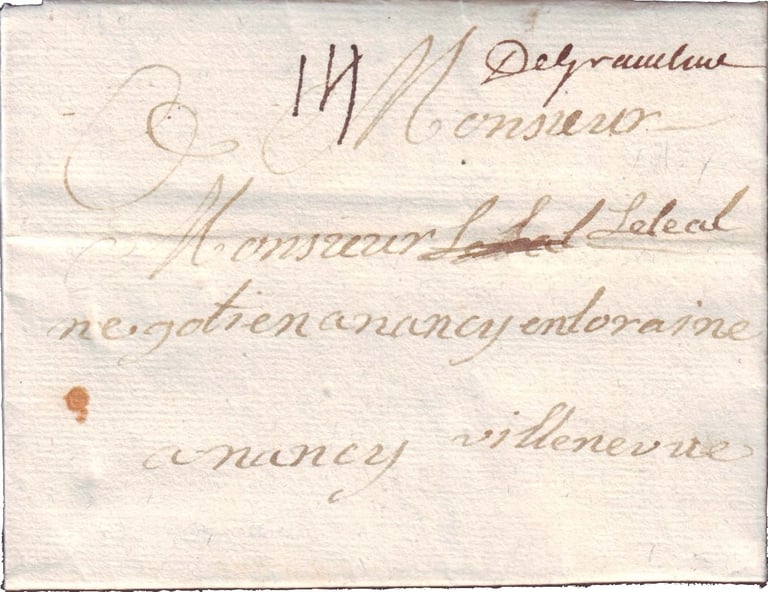

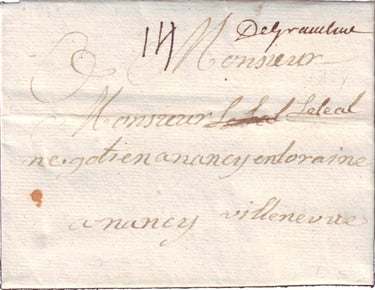

1737, letter from GRAVELINES to NANCY taxed at 14 sols. Lorraine rate of 1730 (single letter routed via PARIS to NANCY).

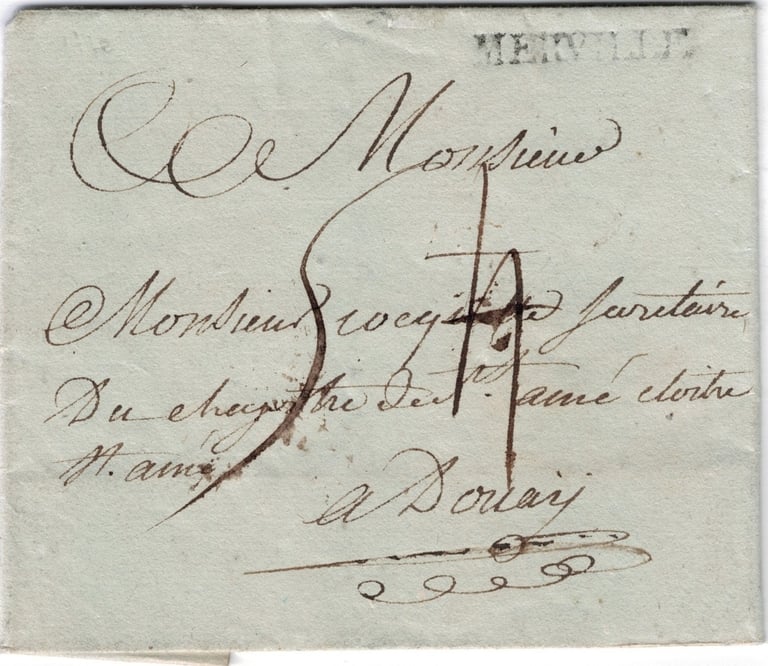

1770, letter from MERVILLE to DOUAI taxed at 4 then 5 patars. Rate of August 1, 1759 (single letter with cover up to 20 leagues). The form of the 4 and the 5 is very similar to that used after the Revolution.

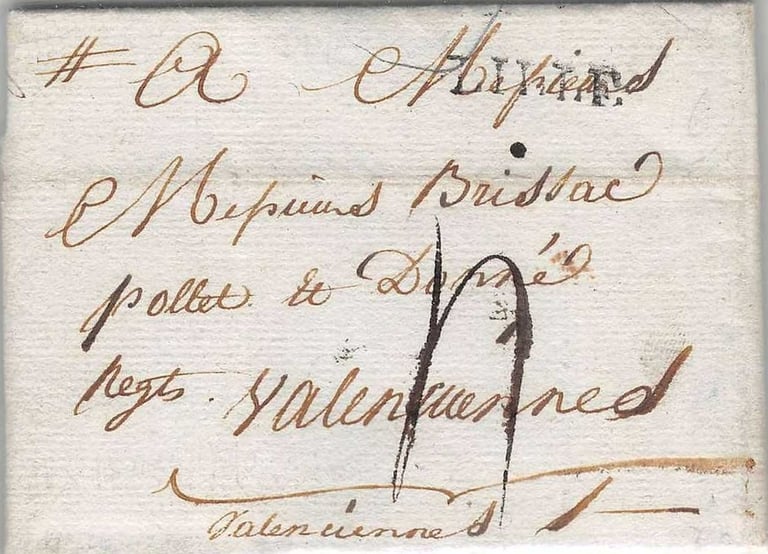

1790, letter from LILLE to VALENCIENNES taxed at 4 sols. Rate of August 1, 1759 (single letter up to 20 leagues in distance). Here too, the form of the numeral 4 is very close to that later adopted by the postal administration.

Table D 2, General Instruction, 1832. Taxes in francs and décimes.

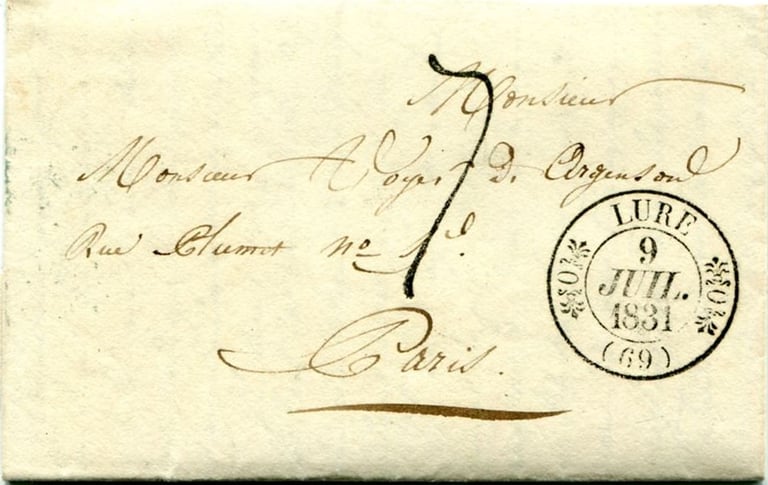

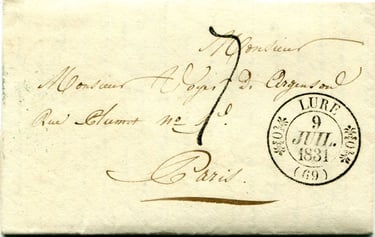

Postage-due letter from LURE to PARIS taxed at 7 décimes (weighing less than 7.5 g over a distance of 333 km). Here again, the numeral 7 on this letter is identical to that in the General Instruction of 1832.

Circular No. 30 of June 2, 1831 informed post offices that they would receive a tax handstamp to be used for taxing single letters (weighing less than 7.5 g) sent from their office to PARIS. The form of the numerals shown on these handstamps was already identical to that appearing in the General Instruction distributed to post offices in June 1832, i.e., one year after Circular No. 30.

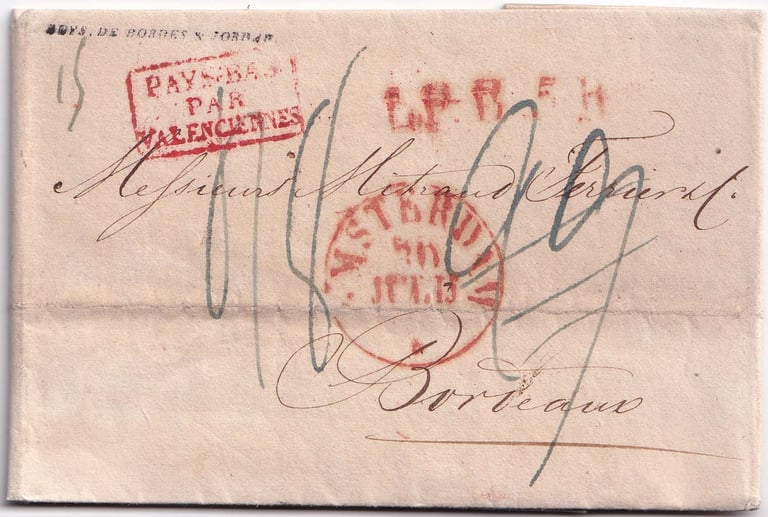

1829, postage-due letter from AMSTERDAM to BORDEAUX, weighing 15 g (handwritten note “15” at top left). It was first taxed 29 décimes, then corrected to 48 décimes.

The tax is broken down as follows:

9 décimes: postage for a single letter from AMSTERDAM to VALENCIENNES, according to the 1817 Franco-Dutch postal convention, with the mark L.P.B. 5 R. (Letter from the Netherlands, 5th Rayon).

10 décimes: postage from VALENCIENNES to BORDEAUX, according to the domestic rate in force since January 1, 1828.

That makes a total of 19 décimes for a single letter.

However, a letter weighing 15 g was equivalent to 2.5 times the postage of a single letter, which gives 48 décimes.

Note: the form of the tax numerals used here (29 and 48 décimes) corresponds to that which would later be formalized in the General Instruction of 1832, although this letter dates from 1829.

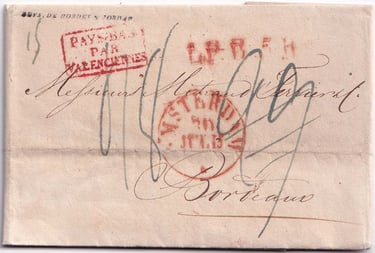

1843, postage-due letter from CHIMAY (Belgium) to MAUBEUGE initially taxed at 3, then at 4 décimes. According to the 1836 France–Belgium postal convention, a single letter bearing the B.1.R. mark (Belgium, 1st Zone) was to be taxed as follows:

2 décimes up to the border,

2 décimes for the domestic route within France.

This gave a total of 4 décimes, consistent with the tax finally applied.

Although the letter bears the date-stamp BELG. (2) MAUBEUGE (2), it actually entered France via AVESNES. In fact, the AVESNES office used two entry marks:

BELG. AVESNES for letters coming from CHIMAY,

BELG. (2) MAUBEUGE (2) for those coming from MONS.

The impression found here is therefore the result of an error in the use of the date-stamp.

1849, postage-due letter from HAMBURG to REIMS. The tax of 9 décimes is explained as follows:

5 décimes for a single letter up to the French border (France–Thurn and Taxis postal convention of 1844),

4 décimes from VALENCIENNES to REIMS (rate of January 1, 1828).

1852, underpaid single letter from CASSEL to OUDEZEELE.

At this date, the territorial rate for a single letter was set at 25 centimes. However, the letter bears only a 10-centime stamp.

The tax of 15 centimes therefore corresponds to the difference between:

the normal rate for an unpaid letter (25 c.),

and the franking already affixed (10 c.).

That is: 25 – 10 = 15 centimes.

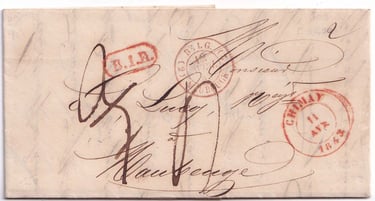

1863, postage-due letter from COLOGNE to LILLE. The tax of 5 décimes, applied here with a handstamp, was set by the 1858 France–Prussia postal convention and corresponds to the postage for a letter up to 10 g.

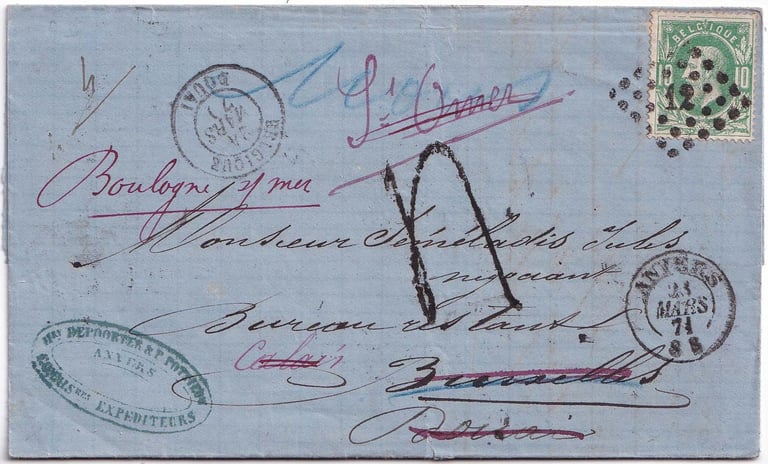

1871, letter from ANTWERP to BRUSSELS (poste restante), redirected to CALAIS, SAINT-OMER, DOUAI, and finally BOULOGNE-SUR-MER.

The 10-centime franking affixed to the letter was sufficient for domestic Belgian postage, but not for transmission to France.

According to the France–Belgium postal convention, the tax on an insufficiently prepaid letter was calculated as follows:

take the postage for an unpaid letter (50 c.),

deduct the franking actually affixed (10 c.),

leaving 40 c., i.e., 4 décimes.

This tax was applied using a handstamp, the form of which corresponded to the prescriptions of the General Instruction.

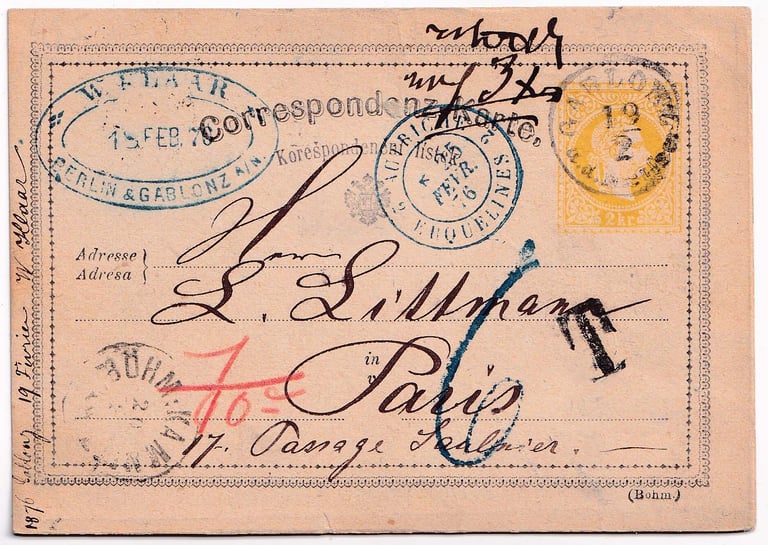

1876, postcard from GABLONZ (Austrian Empire) to PARIS. According to the Berne Postal Treaty of 1874, in force in France from January 1, 1876, an insufficiently prepaid postcard was not to be transmitted. For an international mailing, the required franking was 5 kreuzers.

However, in practice, some insufficiently prepaid postcards were nevertheless forwarded. In the absence of a precise rule for such cases, French postal clerks applied a tax equivalent to that of an unpaid letter, i.e., 6 décimes.

Here again, the tax was applied using a handstamp consistent with the prescriptions of the General Instruction.

Annex No. 13, General Instruction, 1868. The tax numerals shown here are very similar to those of the General Instruction of 1832.